We’re back! And here’s a brand spanking new interview Sean M. Thompson conducted with author T.E. Grau. Take it away, Sean…

What do you think the role of genre is in fiction?

The role of genre is that everything is genre, and nothing is genre. That might sound faux philosophical and ridiculous, and probably is, but it’s what I’ve come to believe, in analyzing how I classify books and stories in my own head based on outside pressures, coming the realization that a) it doesn’t matter, and b) too much is made about genre vs. non-genre, the latter of which is usually referred to as “literary fiction,” as if stories and books tainted with the genre smear are any less literary. I’ve read some poor, incredibly dull writers who are incredibly popular in the “literary fiction” grouping, and read some brilliant, heartbreaking prose that’s been cast down into the basement of genre. I resent the labels, not because they mean anything to me, but because they mean so much to the outside world, and – as a proud writer of so-called genre fiction – I think there is a huge dupe going on, and a tragic disservice.

In a recent “year in review” blog posting, horror author Adam Nevill wrote about recently buying a house through the proceeds of his writing, noting: “Over two decades of commitment to the most unfashionable, and second most derided, genre of fiction eventually paid dividends that I never expected.” Why must one feel this way? Why are very successful horror writers moved to mention such things, even when celebrating success? Because of the very real lack of respect for horror fiction by the outside world, while those on the inside can’t figure out what everyone is not seeing. This was reinforced by a conversation I had just this morning with horror writer Ray Cluley, during which we discussed our frustrations at the reputation worn by “genre fiction,” the near-apologies – or long explanations at the very least – horror writers must make when discussing what they write in mixed company, especially if that company includes writers of what is considered more “literary” fiction. Ray writes some of the most “literary” tales, most of which also happen to be classified as “horror,” that I’ve ever read. But he, too, feels the stigma, the guilt by association. It’s nonsense. But it’s real.

Another example, and more specific to the point: I just finished John Connolly’s masterful Night Music: Nocturnes Volume 2, and the last piece in the book is an essay titled “I Live Here,” in which he discusses how horror fiction, from as far back as its first inception as gothic and supernatural fiction, was seen as somehow lurid and obscene, nearly akin to pornography, or worse – something cheap and certainly not to be taken seriously. This reminded me of how mainstream critics perceived hip hop when it first emerged into the wider public sphere, that it was just some sort of cheap trick, a fad, and not something that merited serious interest or examination. Horror, just like hip hop, is STILL dealing with this sort of second class citizenship, and it angers me greatly, as both are just as worthy – if not often more worthy – of esteem and veneration as weighty and influential members of their particular art form. In looking for an exact quote from this Connolly piece, I came across this bit from the author issued in 2011, published by June Caldwell on her blog Shakespeare Couldn’t Email: “Novelist John Connolly gave a talk at the Irish Writers’ Centre recently on the history of crime writing in Ireland, our problematic relationship with criminality and publishing trends. ‘We have a very peculiar relationship with genre in this country,’ he explained. ‘So few reviewers want to engage with it, they’d rather categorise books they don’t quite get as literary fiction instead.’ Avoiding the subject leads to a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of fiction, a distrust of popularism. ‘Genre is embedded in fiction, if you don’t understand it, then you don’t understand fiction. Novels were always the great populist form, designed to be read by a lot of people; it wasn’t drama or poetry. The idea of high-brow literary fiction as a separate identity is a recent enough (20th Century) notion.’

And these examples of the fallacy of genre occurred just in the last two days, so they are fresh in my mind. There are thousands of examples of this genre-shaming going on, and the reaction to same by those within the genre.

When you truly think about it and parse it down to the atoms, what is genre? Romance? Action? Mystery? Science Fiction? Noir? Western? Horror? What if a story has all of these, in equal measure? Where do you place it on the shelf? What if it has none of these, but nods toward one or more of them? Is that then Literary Fiction? Who decides, and how are these determinations made? Who benefits from these determinations in the end? I think it’s a bunch of malarkey.

All fiction is inherently “fake,” and all well-crafted writing is considered “literature,” so a well written book about a bored suburban househusband who takes up quilting to bring meaning to his life is no better example of “literary fiction” than brilliantly rendered story about alien gods bent on destruction of humanity. A gibbering, six armed monster dismembering a jogger is no more or less “horror” than a businessman doing the same over his lunch break. Which is genre? Which is what subgenre within Genre? It’s all unreal, it’s all fantasy. That one can “actually happen” while the other cannot (are we sure about that?) makes no difference to me.

So, neither does “genre.” What matters, truly matters, is this: Is it good? Does it move you? Are you transported? Does it resonate? Are you entertained? Being boringly realistic, or excessively fantastical or gory or bizarre, can’t hide substandard writing, or save a story that probably shouldn’t have been written, as it’s a complete waste of time for everyone involved. That “genre fiction” is held in the same contempt as B-Movies or straight to video indies in Hollywood irritates me, to say the least. The squares and snoots don’t know what they’re missing.

Wow, didn’t think I’d spend two complete pages on that answer. I guess a bit of venting was in order. So, while my long-winded answer to a very straight forward question might have been a tad temperamental, I think it shows my irritation at the treatment of horror authors in the overall publishing industry.

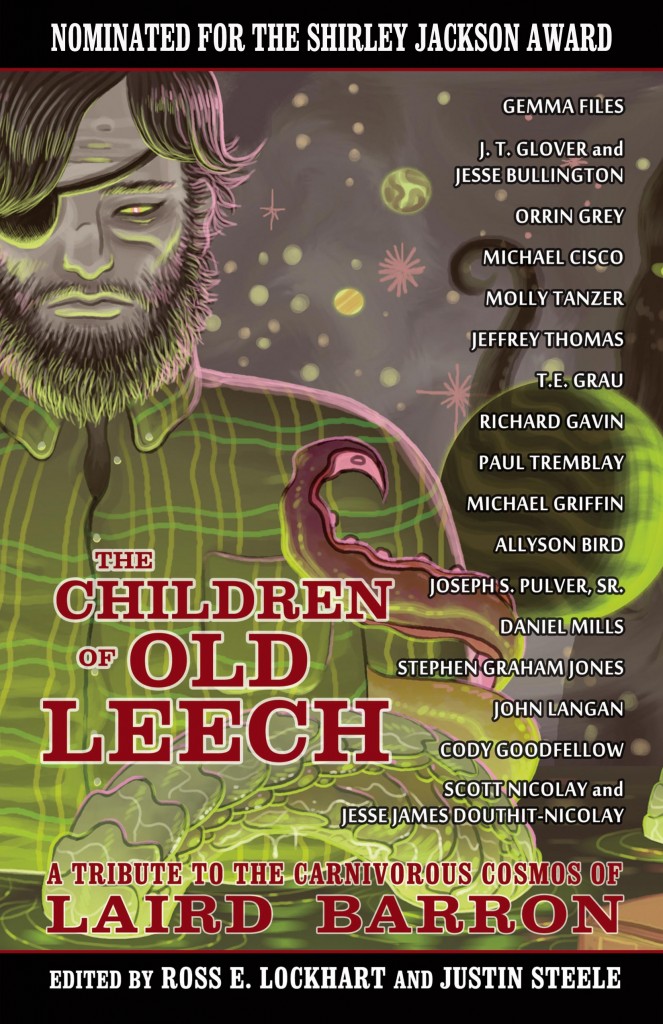

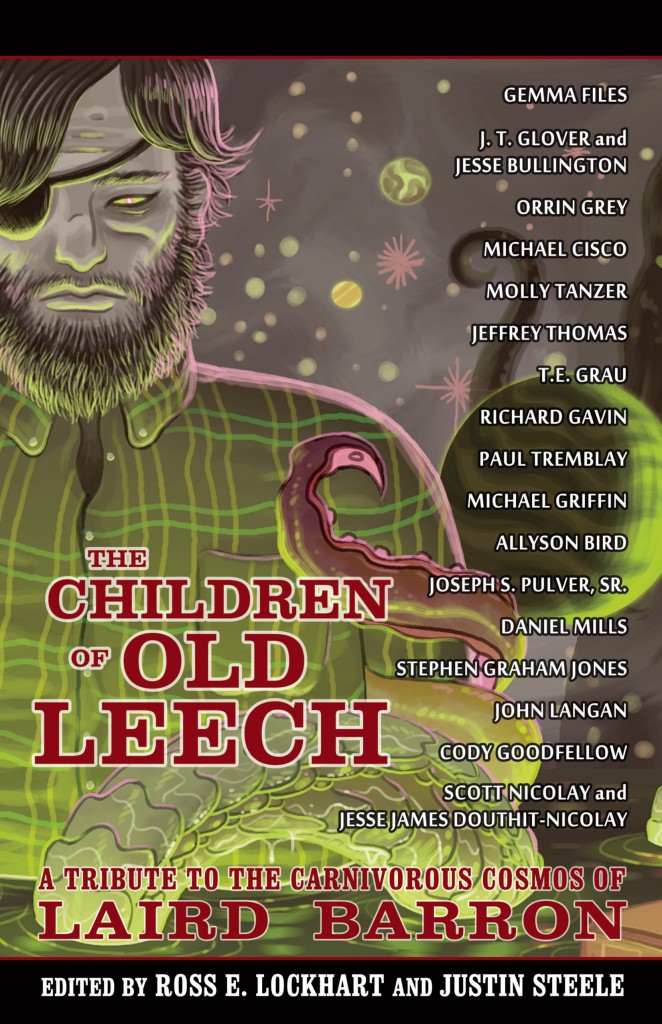

Your story from The Children of Old Leech “Love Songs From the Hydrogen Jukebox,” seems to have, for lack of a better term, rapscallions who take mouth candy and suck at the happy sauce. Is it fun to write beatniks? Also, what inspired you to write this story?

It’s fun to write about Beatniks and their scene to a point, as the enterprise can easily fall into clichéd, 1960’s Beatniksploitation, but I do admire that whole movement, and hold it close to my heart, as reading the Beats inspired me to change my major from pre-law in college to English Lit, which led to me eventually turning my interest to writing books. So, the Beats blessed and doomed me at the same time, which is sort of a Beatnik thing to do.

The inspiration for the story was a tribute to the Beats and City Lights literary scene, coiled inside a tribute to Laird Barron, who has influenced me most recently in my writing. It all seemed to fit together well.

What does the “E” stand for? Are you allowed to say?

Edamame. My full Christian name is Theodore Edamame Grau III.

Do you have anything one might call a ritual you go through when getting into the headspace to play the keys? For instance, do you listen to music, work out, or sit in silence when reaching deep into the ether to pull out configurations of words stitched together for our amusement?

If I’m going to be writing after I get home from work, I listen to music on the way. Something heavy, martial, as I like to gear up mentally. That’s for the actual writing part. Most of my ideas and pre-production have come just after the gym, in that time of walking, showering, and driving between getting ready for work and arriving at the office. Almost everything good I’ve come up with has been created during that morning time period before my brain is pulled into the details of the day job. My story “Clean” came to me almost fully formed in the 90 second walk from my car to the gym. Mornings are important to my initial creative process, that first blush of story. Nights are for finishing.

Do you feel like your surroundings motivate you to write about a certain place?

I don’t know about motivate, per se, as motivation usually comes from within. But, I do feel like my surroundings and the places where I’ve lived and visited have hugely impacted my stories. I live in Los Angeles, and have for many years now, longer than any other location in my life. Because of this, the city features heavily in several of my stories, such as “The Screamer” (Century City, Echo Park) “MonoChrome” (Pico Union, downtown LA), “Twinkle, Twinkle” (Pasadena), “Low Hanging Clouds” (Hollywood Hills, Century City). I’m hammering out a crime (genre!) novel in my head that is set in Highland Park (a section of northeastern Los Angeles), that is mostly about murder, but also explores gentrification and hipsterization of historically blue collar or non-white (I despise the term “ethnic” used as an adjective) neighborhoods. I have two more Noir/crime novels that will be set in Los Angeles, as well, in vastly different parts of the city. LA is such a fertile ground for the dark, the weird, the brutal, and the beautiful. It’s got it all.

I have also lived in Nebraska, and in Pennsylvania (at both ends of the state), and those places show up in my work, too. My novella “The Mission” takes place in the Nebraska Sandhills west of Fort Robinson, and introduces the fictional town of Salt Creek, Nebraska, which is a location that I will be returning to several more times in the future. “Beer & Worms” is set in Nebraska on a farm pond, around the Douglas/Washington County line. The featured couple in “Return of the Prodigy” (from Cthulhu Fhtagn!) is from Omaha.

I think place can have a huge impact on a story, and help color it. As for motivation, and living in Los Angeles, daily witness to one or more of the forty-seven billion screenwriters hammering out screenplays at every coffeehouse and cafe within the city limits can either motivate you to sit your ass down and write along with them, or it can make you never want to commit another sentence to paper, just to avoid the whole cheeseball affectation of it all. It’s a double edged sword, living in a creative town. The energy is palpable, but the execution can be off-putting. Or maybe I’m just jaded.

Do you feel there are any themes you keep going back to in your work?

I do, yes, and it’s not usually conscious, but definitely there. Innocence adrift in a cruel, dangerous world. Individuals alone in a crowd. Failed parenting. Travel as a form of life renewal. The terrible nature of human males. They hypocrisy and tragedy of religion. Misanthropy. Cosmic nihilism. Not all of these are always on the surface, but most of these themes show up in the bios of the characters in my pieces, and therefore inform their actions and reactions.

Thanks for your time, and do you have any plugs for our mugs?

Thank you for the interest! I’m such a huge fan of Word Horde, so I’m stoked to be included on the site.

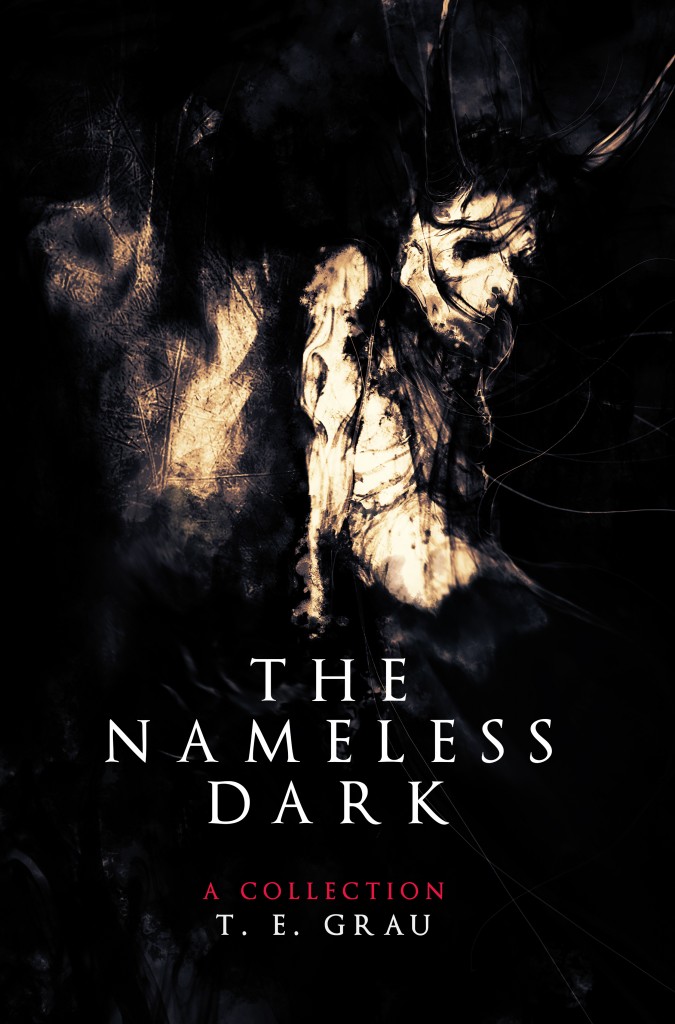

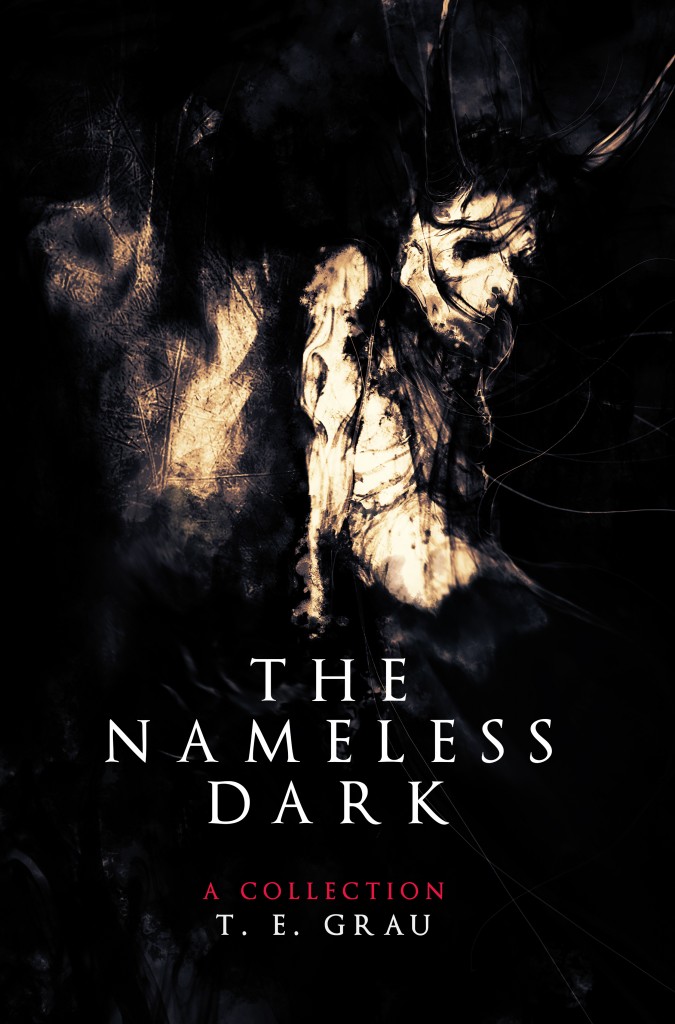

As for plugs, my first fiction collection, The Nameless Dark, is currently available in paperback and e-book through Lethe Press. Stories that weren’t included in the book can be found in the anthologies In The Court of the Yellow King (“MonoChrome”), and Dark Rites of Cthulhu (“The Half Made Thing”), as well as a few other sources that are now out of print and floating around eBay.

I’m finishing the first draft of a novella titled They Don’t Come Home Anymore, a tale of obsession, mortality, and the myth of vampirism, that will be published in 2016 by This Is Horror. A second novella for This Is Horror is also in the works, taking place in a doomsday seed vault near the North Pole, which will also be released in 2016.

Everything else is still too undercooked to discuss, but I’m sure I’ll be yapping about it sometime in the coming year, which promises to be a busy one.