An Interview with Anya Martin

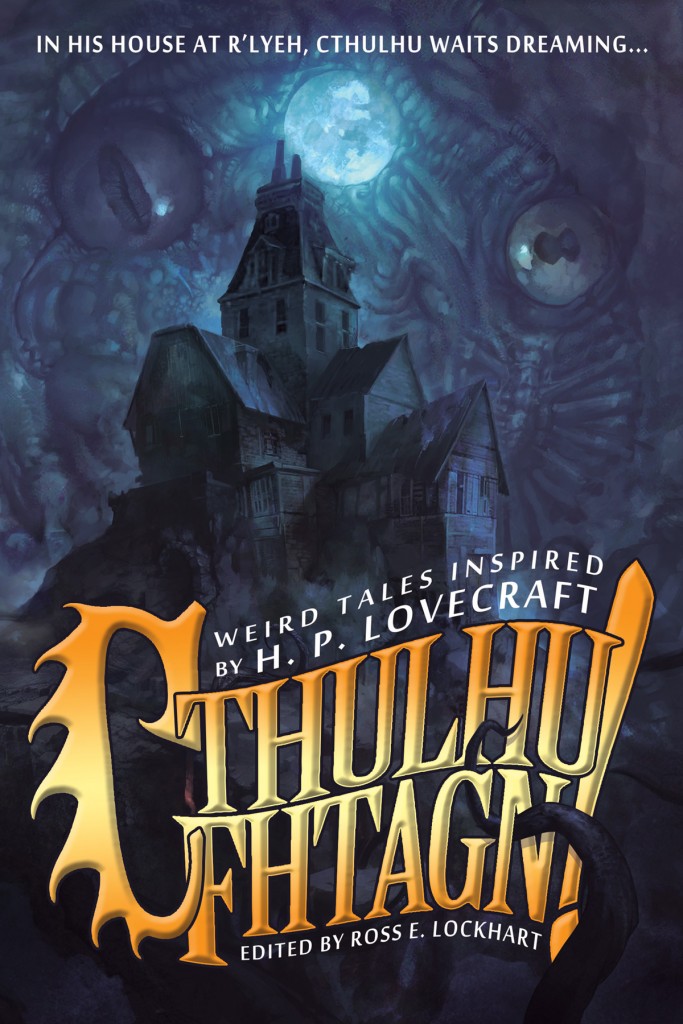

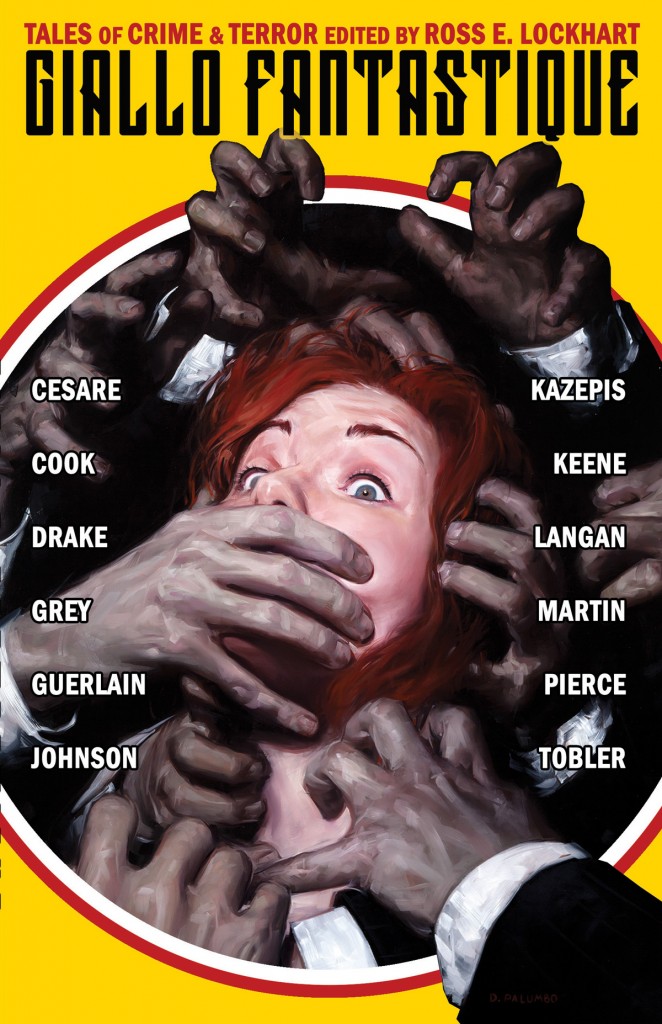

Word Horde’s resident social media maniac, Sean M. Thompson, recently chatted with one of our favorite authors, Anya Martin, whose work has appeared in Giallo Fantastique and Cthulhu Fhtagn! Here’s what Anya had to say…

What do you think the role of genre is in fiction?

That’s a tough one in that like most writers I both hate being placed in a genre box, and yet I am a fierce defender of the claim that spec-lit in all its forms (SF/F/H, etc.) has every bit of legitimacy as literary fiction. I tend to prefer “mode” to “genre” and see the different forms of spec-lit as freeing me to approach realistic topics more, rather than less directly through a fantastic lens. For example in “The Prince of Lyghes,” my story in Cthulhu Fhtagn!, I consciously tackled the destructive impact of alcoholism on a relationship through the mode of Weird horror. The story begins monotonously because the daily life in such a relationship tends towards a constant, creeping dread, but the mode of the Weird allows me to push further into the emotional horror of that daily Hell by giving it a physical manifestation.

I’ll add that I never set out to be a Weird fiction writer per se, but since the recent ascent of the Weird, I have had an easier time selling my work. Before that, I was often told that it didn’t fit. It’d be nice to dream of a day when all books are shelved together and genres don’t matter, but genre classification is also a marketing reality that writers have to live with if they want to be published. Right now, I am fortunate in that editors and publishers seem to be more open to the type of whatever genre I write, whether Weird, horror, dark fantasy, or magic realism. I haven’t written a story I consider explicitly science fiction since “Courage of the Lion Tamer” (Daybreak, 2009), but I grew up loving science fiction and “Sensoria” in Giallo Fantastique actually started as a science fiction story. But that’s another story.

Your story from Giallo Fantastique, “Sensoria,” contained a drug primarily taken at a rock and roll show. What kind of influence does music have on your writing, and have you been to a lot of concerts in your life?

I listen to music constantly, though I stick to instrumental when I am actually writing. A lot of experimental jazz, funk, Krautrock recently filling in gaps because I was such a punk rock girl. My punk/post-punk roots are still on my daily playlist–Patti Smith, the Velvet Underground, Lou Reed, John Cale, Bowie, Eno, Iggy, Ramones, Robyn Hitchcock, Pere Ubu, Wire, The Cramps, to name just a few. And yes, I have been to a fair amount of concerts from local bands to international acts, though not so many stadium-sized shows as I tend to prefer more obscure music. I was also a college radio DJ and music director. I named my show Dangerous Visions.

Music is more of a subliminal than a direct influence in most of my work, though my characters are often listening to music. However, as chance would have it through anthology invitations, I had two stories come out this year in which rock music was integral–”Sensoria” and “Resonator Superstar!” in Scott R. Jones’ Resonator anthology which explores a possible occult side to Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable light/film shows accompanying early Velvet Underground gigs. The latter took a considerable amount of research and came out of attending a re-creation of that experience by a local avant garde film group in Atlanta. I actually wrote the first draft of what would become “Sensoria” around 1990, but its final form was heavily influenced by Goblin and Fabio Frizzi concerts–the latter in a London church on Halloween in 2014. So, OK, yes, my concert experiences, I guess, do bleed directly into my writing. I’m not working on any explicitly music scene stories right now, or wait, I just remembered the novel I am probably writing as my first might have something to do with a dead rock star.

Do you have any writing rituals?

Well, as aforementioned, I do listen to music either before and/or while writing. Otherwise they fluctuate. In the winter, I’ll often drink green or camomile tea depending on whether I need a caffeine lift. I do coffee in the morning but that’s my nonfiction journalism day job time. For “Sensoria,” “Resonator Superstar!” and other stories that I need to tap into a more intense trance state especially as I get near the climax, I have drunk Kava. Some stories come together better in bed with my laptop with scented candles lit, and others sitting at my computer desk–I’m not sure why other than needing a change of scenery. I do usually prefer writing alone rather than in a public place like a coffee shop.

Would you ever eat a bug?

I have eaten bugs! Dried seasoned grasshoppers and still not sure whether those were caterpillars in the soup in China. Also more recently at a natural history museum insect-tasting event, but I can’t remember what kind of insects they were now.

Have you ever written a novel?

I have started novels but have not finished one yet. One in particular keeps knocking around in my brain. It seems manageable in length, I haven’t read anything else like it and fortunately the concept seems saleable. I hope to pick it up again sometime soon, but not until after a novella and I finish up at least three more short stories for anthology invitations.

How do you deal with fear of failure?

I just try not to think about it and keep working. Get the story done and move on to the next one. My brain may be a little too good at compartmentalizing, which is something I may tackle in a future story. On the other hand, right now I also try to keep my fiction goals modest. Get a few more stories completed and sold, see how my work is received, and then hopefully someone will want to collect them. And in due time, hopefully this winter, novel.

Would you consider yourself a fast writer, or a slow writer, in terms of your output.

Haha! Both. I tend to write very rapidly once a story gets going and have been known to complete a story in a day to a week. But I’ll start other stories and there could be long gaps of time as the parts come together in my head. “Resonator Superstar!” and “Old Tsah-Hov” in Cassilda’s Song (edited by Joe Pulver, Chaosium) were both written in two weeks or less, but “The Prince of Lyghes” evolved over three years and even when I thought it was done, I made more changes after a beta reader hit upon something simple and missing that should have been obvious to me.

Thanks for taking part. Anything to plug?

You’re welcome. I do have two more works slated to come out this year–making it a total of six in 2015. My short story, “A Girl in Her Dog,” will be in Issue #2 of Xynobis from Dunhams Manor Press. And Dunhams Manor is also publishing a one-act Weird play called “Passage to the Dreamtime” in its chapbook series. It’ll be the first time a work of fiction by me will be published in a freestanding format, i.e. not in an anthology or magazine, so I’m pretty excited.