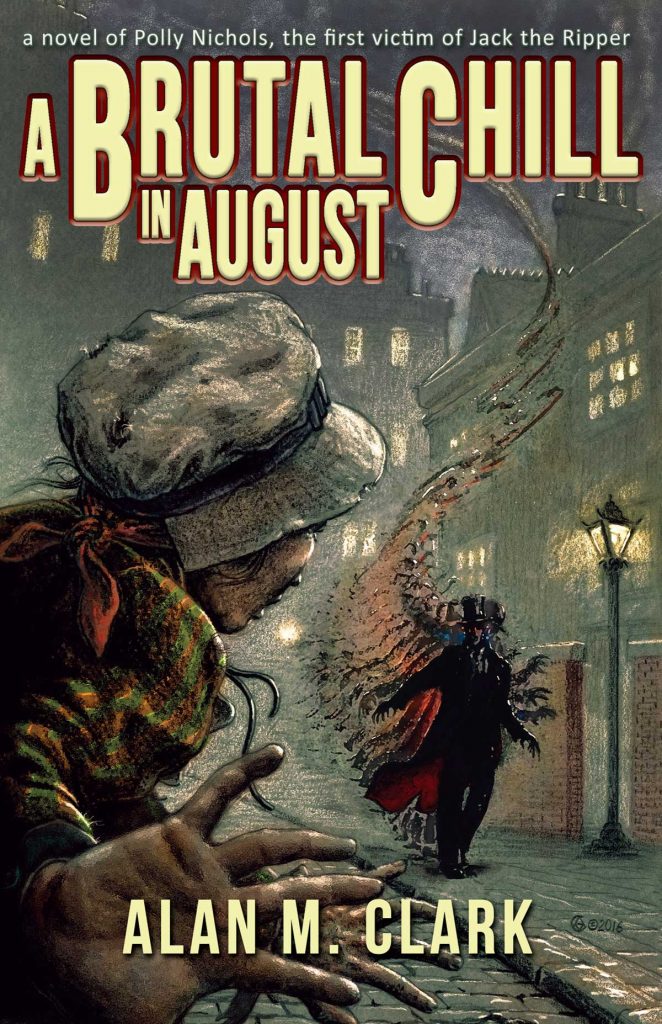

Christmas Ghosts: An Excerpt from Alan M. Clark’s A Brutal Chill in August

One of our favorite Christmas traditions, particularly popular in the Victorian era, is the telling of ghost stories. Something about the long nights of winter, the glistening of ice, and the clouds of breath that form as you step outside evokes the supernatural, the uncanny. Perhaps the most famous of these stories is Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, but other notable Christmas ghosts include Dickens’s “The Signalman,” M. R. James’ “The Diary of Mr. Poynter,” Edith Wharton’s “Afterward,” and H. P. Lovecraft’s “The Festival.”

With all that in mind, Word Horde is proud to present a new Victorian Christmas ghost story, in the form of this excerpt from Alan M. Clark’s stunning tale of Polly Nichols, first victim of Jack the Ripper, A Brutal Chill in August…

13

A Tempting Choice

On Monday morning, December 20 of 1875, Polly hid away the tinplate toys she’d bought for the children’s Christmas stockings—a steamship for John, a train for Percy, a horse-drawn carriage for Alice. As she imagined the children’s faces when they received their gifts, a knock came at her door. She answered the knock to find Judith had arrived early. Dorrie wasn’t with her. The cold and windy air outside tried to push its way in. Judith didn’t respond when invited to come in, so Polly stepped out and pulled the door shut.

“At first I couldn’t decide,” the woman said, “but I have, at present. Dorrie will begin school in the new year. She’s with her grandmother now and during the holidays. No longer shall I come on Mondays and Fridays.”

Perhaps Polly should have seen the day coming, since Percy was the same age as Dorrie, and he had already begun at the infants school. Polly had happily let go of her daytime duties of minding Percy, especially since the discovery she was pregnant again. She hadn’t told Bill or Papa about the pregnancy. Although she loved her children, she didn’t look forward to having yet another so soon.

Her surprise left her struggling unsuccessfully to think of a way to change Judith’s mind. Finally, Polly said simply, “I’m not prepared for the change.” Straining against the chill breeze, she knew she looked as if she might cry. “Could we do it just a bit longer until I can make other plans?”

Judith appeared unmoved. “No, I shall not have a child to keep during much of the week and shan’t need your help. I have plans for Christmas to think about today.”

Indeed, she wasn’t a good friend.

Polly hung her head wearily. “You’re lucky you don’t have the quick womb I have.”

“Are you knapped again?” Judith asked with a frown.

“Yes.”

“It’s not my luck,” Judith said. She grimaced slightly, then asked, “Haven’t you asked Bill to wear a sheath on his manhood?”

“He won’t.”

“Swaine does, and when that fails, I know how to end a pregnancy. There’s a woman can help you.”

“The Church tells us that’s murder.”

“Yes, well, a life unloved and spent in poverty,” Judith said, coldly, “what’s that?”

Polly had no answer. Judith started to turn away.

“Please,” Polly said, “I must have a drink today.”

“And that’s the difference between us,” Judith said. Shaking her head, she turned and walked away.

Polly stepped back inside, and slammed the door, shutting out the biting cold.

The woman’s abrupt manner aside, her suggestion about abortion made Polly uncomfortable because of the tempting option the procedure presented. She considered abortion wrong, and believed that if she took the option, she’d be guilty of murder. Apparently, Judith had chosen just such murders in the past.

Still, Polly believed the life in her womb would be better off if it never saw the world. With each child she’d had, her ability to provide for them, the time she had to share with them, her capacity for affection, and, yes, she admitted to herself, even to love them, had diminished.

What had Judith said? “A life unloved and spent in poverty.”

Perhaps if God knew how Polly felt, He would help. Yet, the Lord should know already what she held in her heart, even if the feelings were a jumble. Polly wanted the best for the three children she had, and if that meant she shouldn’t have another mouth to feed, another heart to soothe and love, then possibly He should take the infant in the midst of her pregnancy. The idea that she might have a miscarriage gave her a small hope which she knew must be dismissed, but which she clung to for fear that if she didn’t, God might not know her preference. The conflict within her turned to nausea. Although most likely mere morning sickness, the discomfort bore with it a chilling uneasiness.

She didn’t have time for such distraction, and tried not to think about the matter further. Her schedule for the afternoon required her to print a broadsheet that advertised a boxing match. She had the materials, including a nicely done woodcut of men preparing to punch each other while others in the background cheered. She needed to take care of Alice first. As she occupied herself, stoking the fire, cleaning the dishes and the pot used to prepare the meal from the night before, nausea and disquiet continued to hound Polly. Her hands trembled and her heart periodically hammered in her chest.

Finally, she promised herself that she’d find a moment to say a prayer for the infant in her womb and one for Judith. That did little to calm her.

She hurriedly fed Alice a midday meal of bread and butter, then placed her in the bed, wrapped in a faded red wool blanket, hoping the girl would take a nap. Before beginning work on her broadsheet, Polly found her moment for prayer. Alice had become quiet, and a calm came into the room, but not into Polly. The conflict in her heart had turned to an unaccountable foreboding. She voiced the words before she’d had a chance to think them through.

“Please O Lord, take this child now before it’s too late.” Polly regretted her plea immediately. While trying to persuade herself that God understood that she meant for the child not to suffer, she knew her true motive to be self-serving. After years of carefully avoiding any mention of herself in prayer, she’d found a new way to demonstrate her selfishness to God. She quickly said the penitent prayer from Mr. Shaw’s well-worn card, but she didn’t feel any better.

Polly couldn’t do her work. Feeling naked before the eyes of the Lord, she paced. When Alice began to stir, Polly knew she disturbed the child’s slumber. She had to get away.

Stepping outside, she had the intention of pacing the lane’s granite footway outside her door. Having traveled half a block up Trafalgar Street, she decided she should keep going. She imagined walking the two or more miles to the docks, and stowing aboard a ship headed to some land where people believed in a different god, one who would not know her so well.

Then, she remembered she’d left the front door open. She broke out in a sweat. Her heart moved uncomfortably as she thought of a stranger entering her room while Alice slept. She imagined John and Percy coming home from school to find nobody home, their confusion and sadness when they found out their mother had abandoned them, and so close to Christmas!

Polly turned and walked back the way she’d come.

Although the shame had become so large inside her that she saw little else, she knew that her children needed her.

* * *

Bill came home from work around noon. His foot had been hurting him for over a week after an accident at the offices of Messrs. Pellanddor and Company. He’d explained on the day of the mishap that a case of letter—a heavy wooden box full of metal type—had fallen from a rack onto his foot.

He hobbled crookedly as he came in, using a cane he’d borrowed from a workmate. “I’m no good at work the way I am,” he told Polly. “Richardson sent me home. Says he’s tired of my curses. I must rest up and go back no sooner than the new year. I think a bone is broken and I should be much longer, though.”

He leaned against the wardrobe, removed his jacket, and unbuttoned his checked waistcoat.

“Alice, make room for your father,” Polly said. “Soon, you must get up and help me impose pages.”

“Yes, mum.” The girl smiled sleepily, and moved over to one side in the bed.

Polly helped her husband lie down. She pulled the shoe off his good foot, then proceeded to more carefully remove the other. He kept his lips tightly closed throughout the process.

“Have you eaten?” she asked.

“Yes,” he said with a strain in his voice. “I can wait ’til supper.”

Polly had missed some of her Monday excursions in the past, when Bill or her father had been ill and not worked for a day or more. On those occasions, with Judith’s help, Polly had always been able to look forward to a time when she’d have a day to herself again. At present, she didn’t know when she’d have another chance to have a drink. Her hands began to tremble as she thought about the problem.

“I’ll need a drink for the pain,” Bill said. “Go around to the Compass Rose and fetch a pint of gin.”

Polly concealed her excitement.

He pulled his purse from a pocket of his trousers and fished out a shilling. “I expect tuppence back.”

Polly took the silver coin. She might not have time to go for a single drink, but she could get a bottle of gin to have on hand at home for herself. Surely, a circumstance would arise in which she might have some secretly.

“Alice, don’t bother your father while I’m gone. He’s not feeling well.”

“Yes, Mum.”

Polly turned away, opened the wardrobe, and used her body to conceal her efforts as she retrieved a shilling from under the loose lining of the left boot of her Sunday high-lows. Pulling on her shawl and bonnet, she left, carrying a basket to hold her purchase. On her way up Trafalgar Street toward South Street, against the bitterly cold wind, she decided that if she ran the whole way, there and back, she’d stay warmer and have the time to drink a glass of stout when she got there. No, Bill might smell the alcohol when she got back.

Even so, she walked briskly. She smiled uneasily at the women she passed, but looked away from each man.

At the Compass Rose, she bought two pints of gin, placed them in her basket, and headed for home, again walking briskly. Polly hadn’t had anything stronger than stout for many years, and looked forward to getting the gin home and finding a chance to take a deep draft.

Bill might see that she had two bottles if she wasn’t careful. The basket held a couple pieces of coarse linen. She arranged the bottles so that each rested under its own piece of cloth. That also kept them from clinking together. When she got back, hopefully Bill and Alice would be asleep in bed. If not, she’d hurry to the larder, a set of shelves within a cabinet built into the wall to the left of the fireplace, set the basket down, and reach inside to take one bottle out. If they were asleep, she’d retrieve the second bottle and hide it away before awakening Bill.

But where?

14

Obsession

Bill was awake when she returned home. Next to him, Alice still napped.

Polly offered a bottle of gin to her husband. He drank half the pint before lying back down on the bed. The remainder of the bottle, Polly hid with the tinplate toys in the back of the wardrobe. Bill might not need any more gin. If he forgot about it, the rest would be Polly’s.

Once he’d begun to snore, she pulled the second pint from the basket, stepped into Papa’s room, pulled the cork from the bottle, and had a gulp of the gin. Although Bill would not smell the drink on her after the lush he’d had, she risked her father noticing when he came home. John and Percy would be home soon, as well.

Putting the cork back in place, Polly returned to her room, having decided to hide the bottle behind the wardrobe. No, Bill could see her when she tried to retrieve the gin if she left it there. She thought to put the bottle in Papa’s room, but decided he knew his living quarters well enough that he’d notice anything amiss and easily find the gin. The eave above the door that led out back had a few broken boards. Perhaps she could hide the gin behind them. If the landlord came to fix the eave unexpectedly, though, he’d discover her bottle. He might well take the gin for himself. Worse, he could ask Bill or Papa about it.

The drink in her belly had created a warm spot that grew. Soon the warmth would enter her head and her worries would flee. She wanted to find a hiding place before that happened.

The privies! She thought that the bricks that lined the floors of the facilities measured a bit larger than the bottle she needed to hide. She grabbed a spoon, stepped out back, and entered the closest privy. Down on her knees, she pried up one of the bricks from the corner beside the door, and found the earth underneath tightly packed. Despite the distance from the seat, the soil smelled of old urine, and she briefly feared the odor might carry with it cholera or other diseases. Undeterred, Polly used the spoon to scoop out enough earth to create a space the bottle would fit into even when the brick was returned to its spot. Settling the bottle into the space, she put the brick back to see if it sat flush with the others. The hole required more digging. She tested two more times before the preparation looked right. Before placing the gin into the hole for storage, she tipped the bottle upside down, making certain the cork sealed well. Polly placed the gin in her excavation, returned the brick to its spot, and worked the soil on top so that the floor didn’t look as if it had been disturbed.

Returning to her rooms, she found Alice up and around. Polly resumed her work on the boxing broadsheet. She gave to Alice the printed pages of a chapbook job to fold.

John and Percy came home, and Polly instructed them to sew the edges of the chapbook pages.

Papa arrived two hours later. Somehow, he knew she’d been drinking.

“Yes, I had a nip after Bill took his fill,” she said, “but it wasn’t much.” She showed him the bottle. “He took half of it.”

“He’s not a drinking man,” Papa said. “He’ll be asleep for a while, then.”

Polly prepared supper and sat with her father and the children to eat. Thoughts of the bottle in the privy distracted her. She worried that one of her neighbors would find it. She worried that the cork would leak; that either the bottle would lose its contents or that the urine of careless visitors to the facility would somehow get into her gin.

The children occupied themselves through the evening with their grandfather, playing simple card games. By lamplight after dark, Polly completed the order of broadsheets for the boxing match. When she’d finished, Papa was asleep in his room with the boys, and Alice slept in bed next to her father. Although he had not completely awakened, Bill had grumbled and shifted a few times on the lumpy mattress. She knew that when he awoke, he’d be hungry.

Polly stripped and put on her nightclothes. She lay down next to Bill and tried to sleep. The gin still haunted her. She imagined exhuming the bottle and having a drink. Once she’d played through the scenario in her head, she couldn’t get rid of the idea, and so she seriously thought it through. Her father was accustomed to having her pass through his room on the way to the privy at night, and easily slept through the sounds of her tread upon the noisy floor. Even so, she feared that as soon as she tried to get to the gin, he’d sit bolt upright in his bed and ask what she was doing. No, he would take no notice of her. She’d go to the privy, dig up the bottle, have her dram, and no one would be the wiser. By the time they all awoke in the morning, the powerful smell would be off her. Polly tried to put the plan out of her head and go back to sleep, but couldn’t.

Finally, she rose, lit a lamp, and pushed her feet into her boots. As she made her way toward the back door, her heart leapt with each pop and squeak of the floorboards. She moved quickly, got to the door leading out the back, and opened it. Stepping through, she discovered bitter cold and frost clinging to everything outside. The full moon rode wisps of cloud, high in the clear sky. She scampered to the privy. The door opened easily.

Polly entered, set the lamp on the seat, pulled up the hem of her nightclothes, and knelt with her bare knees on the cold, hard floor. She found the brick frozen in place. Having forgotten her spoon, she clawed at the floor. Her breath plumed so heavily about her head, she had difficulty seeing. She scraped the skin off her finger tips before the brick finally gave a little. While her fingers stung, she worked at it. After a time, she got the brick loose.

The gin lay undisturbed. The glass that held the potent liquid gleamed like a jewel in the soft orange light. Polly lifted the bottle and pulled the cork. She leaned back against the gritty brick wall of the privy, put the mouth of the cold glass to her lips, and sucked hungrily. Half the contents were gone before she lowered the bottle to the brick floor.

Ignoring the icy chill, Polly closed her eyes and gave the alcohol time to wash over her in soothing waves of intoxication. As she savored the sensation, she lost awareness of the passage of time. Entering a state in which nothing troubled her, she relaxed and decided that if she were discovered that instant, whatever the consequences, she would not care.

She hadn’t had so much gin since she was a girl. The alcohol had a powerful effect. As her intoxication deepened, she had a desire to throw caution to the wind and drink the rest of the bottle. Polly searched with her hands until she felt the cold glass. The bottle rested on its side next to her. Raising the vessel into the light, she saw that most of the gin had drained out.

Realizing she didn’t have a good dose for later, the troubling loss quickly became a tragedy in her mind. As a moan escaped her throat, the door to the privy opened. In her haste she’d forgotten to latch it.

Bill stood in the doorway, supporting himself with the cane. “What are you doing down there? Are you hurt?”

“I—I—” she began, although she had no good answer. Despite her earlier sense that she would not care if she were caught, Polly cowered in fear.

Bill lifted her by the arm. The bottle fell from her lap upon the brick floor with a hollow clink.

Bill inhaled deeply. “You drank my gin?”

“No!” Polly said.

“Don’t lie to me.” Bill dragged her out of the privy as she clawed at the wooden threshold to get away. He threw her down and struck at her with his cane. Polly dodged out of the way and tried to rise. He swung again, and hit her shoulder, knocking her onto her right side. She held her tongue to keep from awakening the neighbors. He landed a solid blow to her ribs that forced a cry out of Polly.

“Quiet,” he said, and struck her in the face. “This is between you and me.”

As Polly got her feet under her, he brought the cane in low, using both hands to plunge the staff into her gut, and knock the wind from her in a great bellow. She fell backwards, striking her head on the cold, hard ground. Her skull seemed to ring like a bell and a taste of iron filled her nose and mouth.

She lay on her side, unable to move for a time, watching as the door to their rooms opened and Papa came out. He looked at her briefly, then spun on her husband and struck him in the face. Bill went down and Papa followed him. He crouched over Bill and struck him in the head repeatedly. Billowing vapor shot out of Papa’s mouth and nose with every angry breath.

As neighbors began to emerge from their rooms to watch, the back lane filled up with people.

Then, Cynthia Dievendorf, who lived two doors down, was cradling Polly’s head.

Gerald Guinn, who lived next door in the opposite direction, tried to pull Papa off Bill. Once her father allowed himself to be hauled away, Polly’s husband seemed a dark, lifeless lump, except for the light, rolling mist of his breath in the cold air. His blood ran black in the moonlight, giving off a lazy vapor of its own.

She knew nothing more until she saw warm daylight coming through the front window of her room. She lay in her own bed. Polly ached all over and didn’t want to face the world. She saw no sign of Bill. Cynthia sat in a chair that had been moved from Papa’s room to a position beside Polly’s bed. Alice sat in Cynthia’s lap.

Before they noticed her wakefulness, Polly closed her eyes and willed herself back to sleep.

15

While She Was Out

The Bonehill Ghost chased Polly for several days and nights through the empty streets of London. With the sun barely visible through the London particular, which hung heavily in the air everywhere, she had a vague sense of the passage of time. Unlike the incident in her childhood, when the demon had chased her with no goal but torment, she knew that this time he’d come to take something from her.

Polly called out for help as she ran. She saw no one and nobody answered. The sound told the demon exactly where to find her. As she tried to find her way home, he repeatedly thrust his devil face at her from out of the choking haze. Sometimes, she heard the slosh of the demon’s bottle, the rattle of its chain around his neck, and his rapid steps behind her. Other times, silently and with his powerful smell masked by the fog, he surprised her, leaping out of hiding with a chortling laugh and a flash of blue flame. To avoid madness, Polly turned away before her gaze and mind fixed on his red, glowing eyes. Mile upon mile of dank, abandoned thoroughfares, mired in horse dung and running with raw sewage, passed beneath her feet. Brooding brick buildings and rotten wooden houses with darkened windows loomed on either side, some leaning so far out over the street, she feared they would fall on her as she passed.

Although Mr. Macklin would have what he wanted, giddy with drink, he prolonged the chase for the fun of it. Polly wanted the pursuit to end, yet was too afraid to allow that for the longest time. Her bare feet became raw and bloody, her lungs choked with poisons from gulping the foul air.

Finally, exhausted, she stopped running abruptly. As she stood gasping for clean air and not finding any, Mr. Macklin dashed out of the yellow pea soup mist, his dark features pinched and twisted into a cruel grin. “You have something of mine,” he said. He didn’t use her father’s voice as he’d done on his first visit. Then he looked down at her gut.

Until that moment, she’d assumed he intended to take her soul. Polly realized too late her mistake. He’d come for something else, a thing precious indeed. She had only an instant of horror to react. Polly tried to turn away. He exhaled a blue flame that blinded her, and snatched the tiny child from her belly with rusted metal claws.

“The soul of you, a hole in you, as what your screams beseech,” he sang in his jeering Irish voice.

While the agony of iron penetrating her abdomen took away all thought, the plucking of the child from her womb brought an emotional devastation that eclipsed physical pain.

Polly awoke screaming and clutching at herself.

* * *

Cynthia Dievendorf lay across Polly, restraining her. “You’re safe,” she said repeatedly.

“My baby,” Polly cried. She bucked beneath the woman. “He’s taken my baby.”

Surprisingly strong for such a small woman, Cynthia held Polly against the straw mattress until the fight left her. The woman’s oily dark locks hung in Polly’s face. Cynthia’s features, at first frightening from the strain of exertion, became calmer. Her warm brown eyes gazed into Polly’s for a moment. Then, they retreated as the woman pulled away and got off the bed.

Polly’s head ached severely. A deep soreness in her muscles suggested she’d lain too long in bed.

She recognized her room. Darkness lay outside the window. The table had been moved from Papa’s room to a position beside the bed next to the chair. A lit lamp rested on the tabletop. A book lay open beside it.

“My baby,” Polly said again, her voice a croaking whisper. She tore open her night gown to look at her abdomen. Instead of claw marks and rent flesh, no more than a faded greenish-yellow bruise marred the smooth skin of her belly, no doubt from the strike of Bill’s cane.

“Lost,” Cynthia said. “I’m sorry. You had a miscarriage. You passed her on your second day in bed.”

Another girl, Polly thought. A sense of loss overwhelmed her and she wept. Cynthia held Polly’s hand.

Bill had no doubt killed the child when he’d struck Polly in the gut. The demon had come after the soul of the little girl, unless his visit had been nothing but a bad dream.

No, that my baby was lost in the nightmare, too, means it was more than a dream.

With her recent prayer gone so horribly wrong, Polly assumed the manner of the loss had been God’s answer, one meant to punish her. She’d turned her own husband into an unwitting child killer. When last she’d seen him, he appeared dead. Had she turned Papa into a killer as well?

I am responsible, O Lord. Please do not punish Bill, Papa, or my unborn for my sin. If the Bonehill Ghost has the soul of my little one, reclaim her spirit and comfort her in Heaven. I shall live in misery for what I’ve done. Amen.

Even as she prayed, she wondered why God would listen to her. Polly wept until her eyes stung from lack of tears. Even then, her sobbing continued.

Cynthia released Polly’s hand, stood, and put a kettle by the fire. “Tea will help.”

Polly gathered her thoughts and ceased to sob. At the first chance, she’d take Bill’s half pint of gin from where she’d hidden it in the back of the wardrobe and throw the bottle into the vault of the privy. She would never drink again. Although abstinence was the logical solution to the bulk of her problems, and she made the commitment without hesitation, she did so with doubts that she would not explore until she felt much better.

Cynthia returned to her seat, and held out a small mirror. Polly reluctantly took it. Cynthia nodded encouragement.

Looking at her reflection, Polly saw no fresh wound on her face. The scar on her forehead—the one she’d got at age thirteen from drunkenly bashing her head against the brick of the lodging house—appeared red and sore, but didn’t feel tender when touched. She’d received the wound on the evening of her first encounter with the Bonehill Ghost. Polly wondered if her second encounter with the demon had turned the scar red.

As the water began to boil, Cynthia returned to the fireplace.

“How long have I been here?” Polly asked.

“Seven days. A doctor came. He said if you didn’t awaken by Wednesday week, you ought to go to hospital. Today is Wednesday. Your father were preparing to take you in his barrow tonight.”

“My children—”

“—are with your husband.”

Polly had intended to ask about Bill next.

“I believe he has found a new home for you and the children,” Cynthia said. She measured tea into two cups.

So Bill had recovered enough from the beating Papa had given him to be out looking for a new place to live.

“My father?”

“He’s here each night—should come home in a few hours.”

Papa hasn’t been hauled to the drum and locked up.

Would Bill send her away with the children to live somewhere else? If so, where would he live? No doubt he wouldn’t want to stay with Papa.

Polly thought of the tinplate toys for the children, hidden away in the back of the wardrobe. “Did the children have Christmas?”

“I don’t know. They were away with Mr. Nichols. I believe he is with his sister.”

Bill hated his sister, Rebecca. Polly knew he must have truly wanted to escape to seek her help.

Polly choked back shame as she thought of how she’d spoiled Christmas. She didn’t want to think about the children’s disappointment. If they hadn’t received their toys, perhaps she might yet see the surprised delight on their faces. She supposed that depended on how much they knew about what had happened.

“You’ve been here—” Polly began.

“Since that night,” Cynthia said. Crouched on the hearth beyond the foot of the bed, she poured hot water from the steaming kettle into the cups. “I lost my baby boy the day before, and needed to do some good for my own heart.”

Polly watched a tear fall from Cynthia’s eye and catch the firelight. The woman quickly wiped the droplet away.

“I’m sorry,” Polly said. She knew Cynthia’s husband was away in the Orient with the Royal Army. “Thank you for staying by me.”

Cynthia smiled miserably.

The Lord might not hear me, Polly thought, but an unselfish prayer couldn’t hurt if it came from the heart.

She thought her words through carefully before beginning.

Loving God, help Cynthia’s heart to become whole again. Care for our infants, taken before they had a chance at life. Polly followed that with the penitent prayer.

—

A Brutal Chill in August is available now from Word Horde. Ask for it by name at your favorite local bookstore.