Jack London (1876-1916)

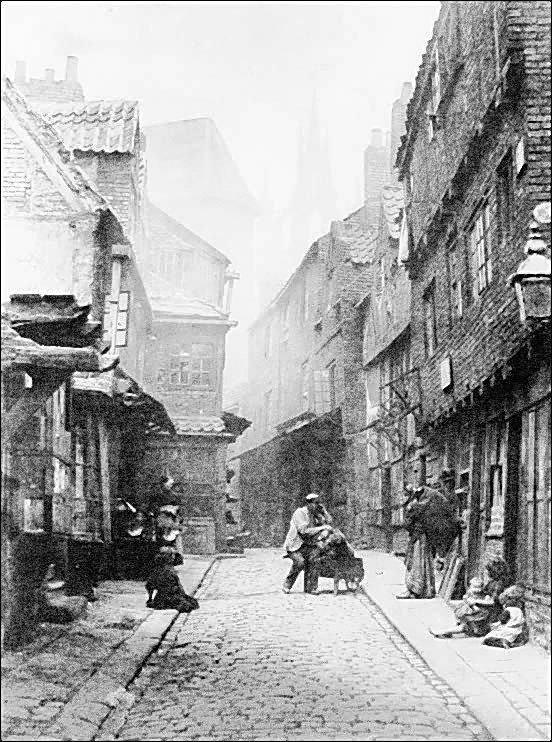

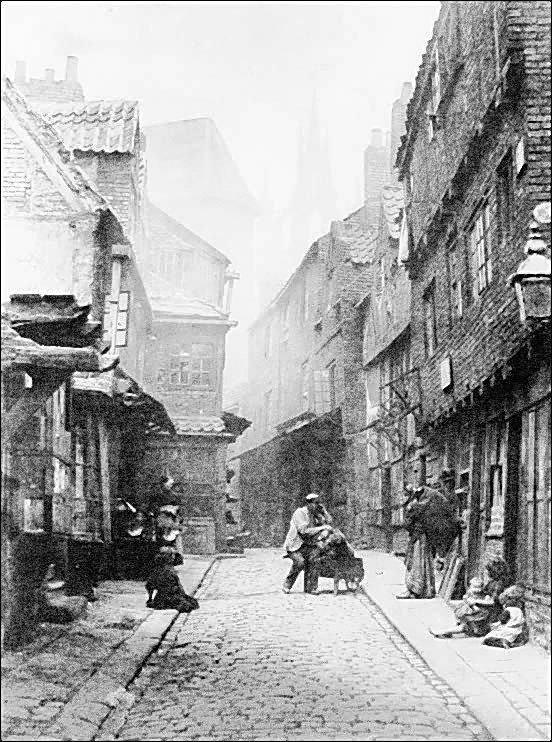

In 1902, the year following the death of Queen Victoria , which of course ended the Victorian era, Jack London, disguised as one of the city’s poor, went to stay in the East End of London. He was there to get first hand experience of a place notorious for its crime, squalor, and increasing human degradation. At the time, London was the largest and wealthiest city in the world. His book, The People of the Abyss, a piece of investigative journalism, is his account of that experience.

The squalid conditions of the East End are enumerated in the Preface, painting a picture that provides me with eye-witness confirmation of much of what I’ve learned in researching the environment for my Jack the Ripper Victims series of novels, including A Brutal Chill in August, soon to be released by Word Horde in August. By 1902, fourteen years after the end of the JTR killings, the East End of London had become more dangerous, more densely packed with humanity than it had been in 1888.

In the first chapter, Jack London describes the difficulty he had in finding help in merely setting up his investigative endeavor. His friends, colleagues, and even those he tried to engage professionally wanted nothing to do with his effort for fear that he headed toward certain doom. Finally, he found a private investigator in the East End who agreed to vouch for him if his body were to turn up. With that, Jack London bought second hand clothes of the ragged variety commonly worn by those in the area, and then disappeared into the East End.

At that point in his life, Jack London, born John Griffith Chaney, was a successful author. He’d done well selling his fiction to the growing magazine markets. For a quick biography of Jack London, try Wikipedia. Although an adventurous sort who’d been to sea, lived as a tramp, spent time in prison, been a laborer, and experienced his share of hardships in life, he currently wore nice clothing and could afford fine food and lodging.

He refered in the book to the difficulties Americans (I assume he means those identifiable as middle or upper class individuals) had visiting British and European cities without losing their shirts to the hordes who contrived assistance for the traveler and then expected gratuities for even the least effort. After shedding his finer clothes in favor of the common rags of the street, the unctuous bowing and scraping of the lower class and the poor, which of course was the vast majority of the population, ceased.

The class system that still thrived in Europe, largely also existed in the United States, yet was tempered by the fact that we did not have a noble class, ruling aristocrats that earned their station merely by the accident of their birth. The gap between the haves and have-nots in both America and Great Britain was large, but no more so than in London. The Industrial revolution had led to large-scale unemployment, much the way the Tech Revolution has done in America and elsewhere today. During the bulk of the 19th century, the city of London, like large American cities at present, suffered from overcrowding and large numbers of unemployed and homeless. Those with little were careful not to displease the upper classes. Quite the contrary. The poor, referred to as “the unfortunate,” and the lower class, when in the presence of their “betters,” often effusively praised those of a higher class and pretended to defer to them in all things for fear of losing employment, reputation, or any other form of possible favor. Frequently, life, liberty, and access to shelter and sustenance depended on behaving that way.

The class system that still thrived in Europe, largely also existed in the United States, yet was tempered by the fact that we did not have a noble class, ruling aristocrats that earned their station merely by the accident of their birth. The gap between the haves and have-nots in both America and Great Britain was large, but no more so than in London. The Industrial revolution had led to large-scale unemployment, much the way the Tech Revolution has done in America and elsewhere today. During the bulk of the 19th century, the city of London, like large American cities at present, suffered from overcrowding and large numbers of unemployed and homeless. Those with little were careful not to displease the upper classes. Quite the contrary. The poor, referred to as “the unfortunate,” and the lower class, when in the presence of their “betters,” often effusively praised those of a higher class and pretended to defer to them in all things for fear of losing employment, reputation, or any other form of possible favor. Frequently, life, liberty, and access to shelter and sustenance depended on behaving that way.

Surely as one who had been a laborer of humble beginnings, Jack London knew quite well the social mechanisms involved, but the sudden contrast with merely changing his clothes—his costume so to speak—was so sharp-edged that he couldn’t help but take notice in his text. Suddenly, the average person on the street was “real” with him. He was treated as a regular guy, trusted with honesty and welcomed warmly into conversation and confidence. As downtrodden as many of the denizens of the East End were, they also had a hardy lust for life they willingly shared with one another.

Makes me wonder how many within the upper classes knew that such warmth and good feeling existed among common people—that sense of camaraderie within the struggle for existence—and if they knew, what they thought about it.

When I was still living in Nashville, Tennessee, where I grew up, I remember a middle-aged white fellow telling me that he’d gone to a church attended almost exclusively by black parishioners, and how surprised he was to see such a nice clean place, with all the people there happy and having a good time with one another. He probably didn’t realize that he sounded like a bigot to me.

Class barriers born of our strange need to stereotype still exist in the world today, ones meant to wall off the undesirable, having to do with anything from skin color, gender, sexual orientation, religion, to politics. Since the broader society often does not accept that such barriers should exist, silent conspiracies are required to build those walls. They are more a product of personal opinion, less formalized and institutionalized than that of the class system of the Victorian period.

I do not know if the middle-aged fellow talking about the black church was a bigot. Perhaps he was just woefully ignorant. But I’d had such things said to me by people who looked me in the eye after speaking as if to carefully assess my reaction, I believe to determine if I was with them; to see if I thought the same way. I don’t tend to react well to people trying to make others into “Other.” I have seen some people respond positively to that sort of crap. When I do see that, I always feel a little dirty and have the sense that a silent conspiracy has just picked up a new member or that existing members have made themselves known to one another.

When Jack London stayed in the East End, the haves and have-nots were segregated—many public places didn’t allow access to those below a certain station. An establishment, like a tavern or inn, often had separate sections for classes to keep those of a higher station from suffering the proximity of those of a lower station. By saying, “suffering,” I’m being sarcastic for effect. Inevitably, the less fortunate and the poor had developed their own culture and shared little of it with the upper classes. Does that seem familiar? It’s a pattern of reaction that can be seen in numerous marginalized groups of minorities throughout the world. In the case of the London poor, though, they were in fact the majority.

I’m intrigued to read London’s honest words about it from so long ago.

Next post on Wednesday July 6, 2016 will deal with Chapter 2.

—Alan M. Clark

Eugene, Oregon

Get a free ebook copy of The People of the Abyss from Project Gutenburg—available in various formats including Kindle and Epub, : http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1688

Preorder A Brutal Chill in August

Visit Alan M. Clark online: www.alanmclark.com

About Alan M Clark

Author and illustrator Alan M. Clark grew up in Tennessee in a house full of bones and old medical books. His awards include the World Fantasy Award and four Chesley Awards. He is the author of seventeen books, including ten novels, a lavishly illustrated novella, four collections of fiction, and a nonfiction full-color book of his artwork. Mr. Clark’s company, IFD Publishing, has released 44 titles of various editions, including traditional books, both paperback and hardcover, audio books, and ebooks by such authors as F. Paul Wilson, Elizabeth Engstrom, and Jeremy Robert Johnson. Alan M. Clark and his wife, Melody, live in Oregon. www.alanmclark.com