Dark Annie

The black eye was healing, but still ached. Dark Annie had Eliza Cooper to blame for that. Something about a purloined penny, some stolen soap, and that handsome pensioner, Edward Stanley. The details were fuzzy for Annie sometimes, particularly when drink was involved, though the bruises were real. This had been a tough year. John had died on Christmas, drank himself to death, then Siffey left her once the money dried up. Annie had been forced to make her living where she could, and when embroidering antimacassars and selling flowers didn’t pay bed and board, she earned what she could on the streets. Her lungs ached, and she wanted one of her pills, but she was down to just two, secured in a corner torn from an envelope because her pillbox had broken. Friends called her Dark Annie because of her dark, wavy hair. In contrast, she was a pale woman with blue eyes, short and stocky. Annie was forty-seven years old.

It was just past midnight on Saturday, September 8, 1888. Annie shared a beer in the kitchen at Crossingham’s Lodging House with Frederick Stevens, then chatted with William Stevens, both fellow lodgers at Crossingham’s. She left for her room, but changed her mind and went out into the night. Around one-forty-five, Annie returned, eating a baked potato. She explained to lodging house deputy Tim Donovan and night watchman John Evans that she didn’t have her rent money, and asked that they hold her bed until she could earn enough on the street.

At five-thirty, Elizabeth Long, a cart-minder, was walking down Hanbury Street toward Spitalfields Market. The clock at the Black Eagle Brewery chimed as she passed No. 29 Hanbury Street, briefly making eye contact with Dark Annie, chatting up a dark, “shabby genteel” fellow in a deerstalker hat. Mrs. Long overhears their conversation as she passes, the man’s ardent “Will you?” Annie, in reply, whispered “yes.”

Elizabeth Long is the penultimate person to see Dark Annie alive.

Annie Chapman’s murder was particularly violent. Her throat had been cut from left to right. She’d been disemboweled, her intestines thrown over her shoulders. Her uterus had been cut out and removed from the scene. At the September 10 police inquest, Dr George Bagster Phillips described the murder weapon: “The instrument used at the throat and abdomen was the same. It must have been a very sharp knife with a thin narrow blade, and must have been at least 6 to 8 inches in length, probably longer. He should say that the injuries could not have been inflicted by a bayonet or a sword bayonet. They could have been done by such an instrument as a medical man used for post-mortem purposes, but the ordinary surgical cases might not contain such an instrument. Those used by the slaughtermen, well ground down, might have caused them. He thought the knives used by those in the leather trade would not be long enough in the blade. There were indications of anatomical knowledge…”

Police made several arrests following Annie’s murder, suspects included a cook, a butcher, and a hairdresser. But none of these panned out. The press, still reeling from the murder of Mary Ann Nichols, continued to sound an accusatory drum for Leather Apron, but within a few weeks, a new name would come to the forefront in the case, a named signed to a series of letters taunting the police. That name? Jack the Ripper.

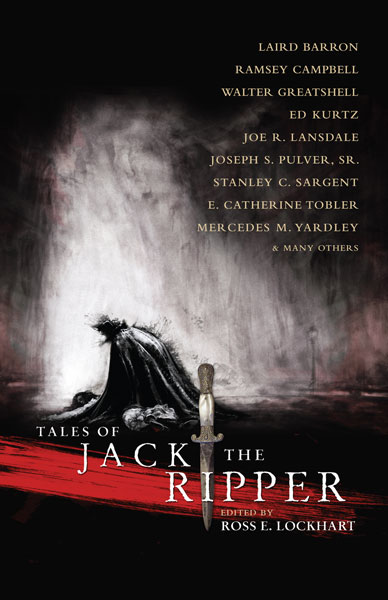

This post is brought to you by Tales of Jack the Ripper, an anthology of seventeen stories and two poems examining the bloody legacy of the most famous serial murderer of all time. Ask for Tales of Jack the Ripper by name at a bookseller near you, or order the Saucy Jack Deluxe Pack from Word Horde.