The Children of Old Leech: Afterword

Today brings the final installment in our series of excerpts from The Children of Old Leech. We hope you’ve enjoyed these excerpts as much as we’ve enjoyed bringing them to you, and we sincerely hope that we’ve persuaded you to pick up a copy of The Children of Old Leech for yourself. And while this round is over, we will be back with more samples of Word Horde books, photos, reviews, and previews, so we would encourage you to stay tuned. So with the melancholic sense of a journey’s impending conclusion, but no regrets, we bring you a look behind the curtain with co-editor/publisher Ross E. Lockhart’s “Afterword.”

—

One of my first gigs in this crazy business we call publishing was writing the flap copy for the hardcover edition of Laird Barron’s first collection, The Imago Sequence. As I recall, I got paid in books for this, which is fine because I’d likely have spent any monetary compensation on books anyhow.

The Imago Sequence blew me away. I was already fairly well versed in the weird tale, and in the typical tropes associated with Lovecraftian pastiche, but Barron’s approach did something unexpected with the form, fusing the strangeness of supernatural horror with the stark naturalism of Jack London (whose “To Build a Fire” Barron himself classifies as Cosmic Horror), daring to deliver something different, a high-stakes carnivorous cosmos populated with tough, rugged protagonists more accustomed to inhabiting hard-boiled tales of crime or espionage than Lovecraft’s prone-to-fainting academics. Through this (at the time) unlikely combination, Barron managed to, in the words Ezra Pound once pinched from a Chinese emperor’s bathtub, “make it new.”

One does not read a Laird Barron story so much as one experiences it in a visceral manner. A tale like “Shiva, Open Your Eye” strips away a reader’s reason, flaying him, leaving him floating in the primordial jelly, innocent of coherent thought. “Hallucigenia” is, quite literally, a kick in the head. The painstaking noirish layering to be found in “The Imago Sequence” culminates in a ghastly, shuddering reveal of staggering proportions. And it is that sense of culmination one finds echoing throughout Laird Barron’s work, binding the whole together into a Pacific Northwest Mythos reminiscent of, but cut from another cloth entirely from, Lovecraft’s witch-haunted New England.

A handful of one-off copywriting gigs led to greater opportunities, and soon, I found myself working full-time for the publisher of The Imago Sequence, which led to my meeting Laird in the flesh at the World Fantasy Convention in Saratoga, NY. I found we shared a kindred spirit… and a taste for rare spirits and supernatural tales. Upon my return, I worked on the trade paperback edition of The Imago Sequence, and on Laird’s next collection, Occultation, where I not only wrote the jacket copy, but laid out the book, coordinated the production team working on it, supervised copyedits, approved those edits with Laird, and corrected the book (as a nod to Robert Bloch, I suppose you could refer to me as “The Man Who Corrected Laird Barron.”).

Shortly after Occultation landed, my wife and I embarked on a road trip up the West Coast, a drive where the scenery—stark mountains, tall trees, steep costal drop-offs—constantly reminded me of one Laird Barron story or another. Our journey brought us to Olympia, where we met Laird for lunch, talked martial arts and American literature, and I snapped a few photographs of Laird playing with our little dog, Maddie.

Somewhere along the line, both The Imago Sequence and Occultation managed to win Laird his first and second Shirley Jackson Awards, and I began working with Laird as editor of his first novel, The Croning, which he sent to me in bits and pieces over the course of a tough year, building it like a wall, brick by brick and layer by layer. With The Croning, Laird metaphorically opened a vein and bled words onto the page, and while a casual reader might not spot the author’s open wounds, the emotional wallop delivered by the book more than assures you that those wounds are not only there, but that they are raw.

I published Laird’s novella “The Men from Porlock” in my first anthology, The Book of Cthulhu, and his “Hand of Glory” in my second, The Book of Cthulhu II. And over the course of 2012, I worked on Laird’s third collection, The Beautiful Thing that Awaits Us All, reading stories as Laird finished them and sent them along. One of my favorites in the collection, the wickedly sardonic “More Dark,” managed to get me in trouble when I read it on my phone during a baseball game, prompting my wife to elbow me as I laughed—then shivered—at a situation that rode the train from bad to weird to worse to a downright Barronic level of darkness. The Beautiful Thing that Awaits Us All was the final project I worked on for its publisher, which might bring us full circle, were it not for the fact that this circle, like the sigil marking Moderor de Caliginis, is an open—and hungry—curve.

In 2013, I started my own publishing company, Word Horde, launching the press with Tales of Jack the Ripper, an anthology that included Laird Barron’s tour-de-force “Termination Dust,” a fractured narrative not only providing the thrills and chills expected from Barron’s oeuvre, but marking a new venue for his brand of cosmicism, a strange, savage, and sanguine land that Laird knows quite well… Alaska.

Not long after the publication of Tales of Jack the Ripper, Justin Steele, who had reviewed The Book(s) of Cthulhu and Tales of Jack the Ripper at his weird fiction website, The Arkham Digest, approached me suggesting this anthology. I receive—and say no to—a lot of anthology pitches, many of which are suggested as possible co-editorial projects, but I found the idea of honoring Laird, an author whose work has influenced and intersected with much of my professional career, irresistible. I approached Laird, asking for permission to let other authors play in his sandbox, and to my delight, Laird said yes. For that, Justin and I owe Laird a lifetime of gratitude. We immediately set to building a roster of our favorite authors, authors who we felt shared Laird’s vision of a ravenous universe, and an understanding of that terrible, beautiful thing that awaits us all.

There are no accidents ’round here. The editors of, and the authors included in, this volume have been inspired and affected by Laird Barron’s carnivorous cosmos. We’ve all gazed at mysterious holes, wondering where they lead. We’ve all found ourselves in conversation with a stranger, staring at a scar and wondering if it is, instead, a seam. We’ve all heard the voices whispering in the night, praising Belphegor, and saying, “We, the Children of Old Leech, have always been here. And we love you.”

—

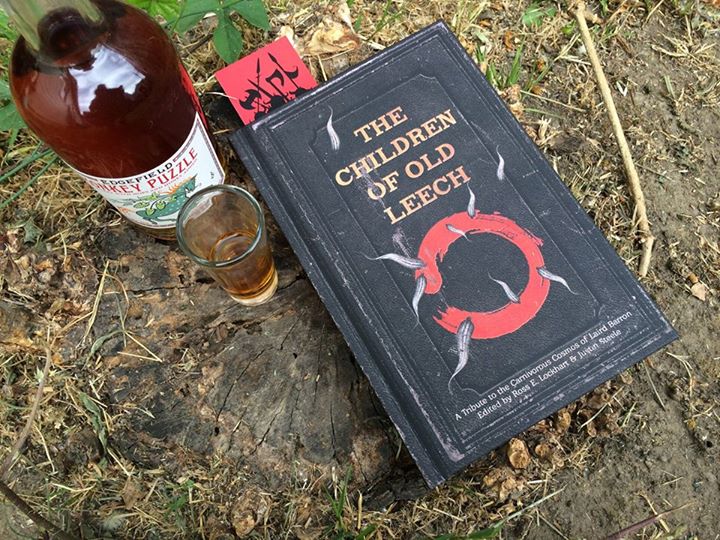

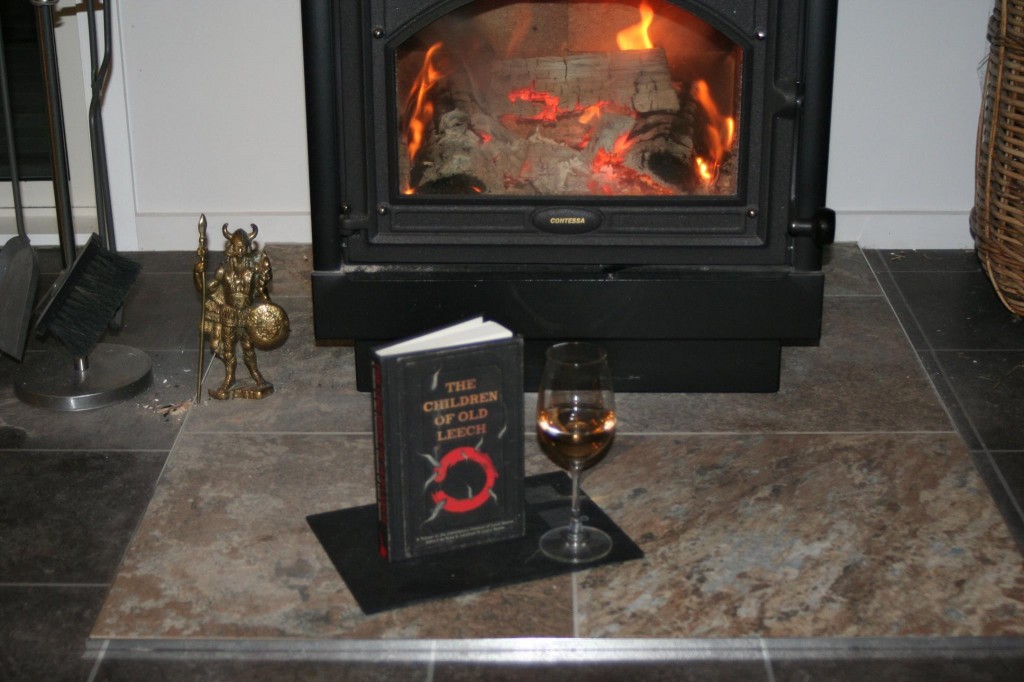

The Children of Old Leech: A Tribute to the Carnivorous Cosmos of Laird Barron may be ordered directly from Word Horde or wherever better books are sold. Ask for The Children of Old Leech and other Word Horde titles at your favorite bookseller.