THE PEOPLE OF THE ABYSS Liveblog Part 10

In Chapter 10, Jack London slept rough to see what that was like for the homeless.

One can imagine that sleeping rough in a large metropolitan area with lots of parks would be something like going camping. If it was a nice warm evening, a sleeping bag (modern term) wouldn’t be needed. If it wasn’t raining—something unpredictable in a London summer—the nice soft lawn of a park would make a good resting place.

Except that the police, along their beats, checked the parks for those sleeping rough at night. So find some shrubbery and hide amidst them and doze off, right? No, the parks had guardians who patrolled them at night. They knew all the spots where the homeless tried to shelter. If they found someone, they alerted the nearest beat constable.

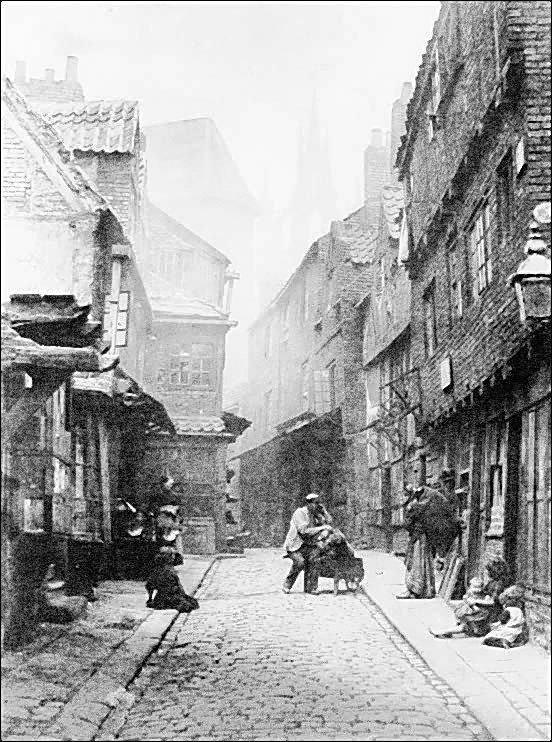

Okay, so no soft lawn, shrubberies didn’t work; parks in general were out. Perhaps the streets had something: alleys, doorways, sewer grates, culverts, railway bridges and viaducts. Unfortunately the constables knew their beats so well all likely sleeping spots were well-known and checked regularly.

Why weren’t the homeless allowed to sleep at night? Clearly, the law did not allow them to do so in public places. Jack London is similarly stumped by this. If the idea was to make the homeless life so uncomfortable that people would get jobs—assuming that any became available—the law or ordinance against sleeping rough at night worked against it. Obviously, a well-rested person who could actually perform labor during the day would more easily find work. Without that consideration, the effort to keep the homeless awake seems at best arbitrary, at worst a particularly cruel one.

Perhaps a notion about the lower class and poor that was carried by many from a higher station played a part; that unfortunates deserved what they got in life because they were inherently inferior and morally corrupt. They were all “choke artists” and “losers,” to use more modern terms. Implied in this thinking is the idea that evidence of the poor’s inferiority was the fact that they had landed hard on the streets in the predicament in which they found themselves. That’s circular thinking.

Trying to sleep rough in London at night, one might get 10 minutes of sleep at a stretch, 30 if lucky, but what was the quality of that sleep? It had to be spent in an environment full of vermin; rats, mice, flies, and scavengers; hungry humans, dogs, and cats.

In a time when the majority of travel that didn’t occur on foot was still powered by horse—hundreds of thousands of them in London of the time—the streets were mired each day in at least a thousand tons of horse dung and over a hundred thousand gallons of horse urine. That had to smell bad.

Much of the manure in London was gathered by scavengers and hauled away for use in agriculture and industry. London would have been totally mired in waste if not for the scavengers. While unemployment had become an increasing problem, the poor, both adults and children, scavenged and sold what they found. The pure finders scooped dog poop for tanneries. The bone grubbers collected bone for the makers of fertilizer. Toshers scavenged in the sewers. Mudlarks, many of them children, scavenged on the banks of the poisonous River Thames. Metal, stray bits of coal, leather, and cloth were all sellable.

Despite the army of unemployed scavenging for industry, much horse dung remained on the streets long enough for flies to breed in it.

I remember my father who was born in the 1920s talking about flies in “the old days.” One of the things he said was that before horses were gone from the streets in Nashville, Tennessee, there had been a lot more flies. “Flies everywhere,” he said, “getting into everything.” Of course that was Nashville, Tennessee when it was a small city in a county of a couple hundred thousand people, not the London of millions.

The average lifespan of a horse in London at the time was about 3 years. Flies also bred in the carcasses of horses, which were often left where they had fallen dead at least until rigor mortise relaxed to make dismemberment and carting away of the remains easier. The flies needed food, and visited every moist aperture they could find, spreading diseases like typhoid fever.

Here is an illustration from Punch Magazine that gives a sense of the poisonous environment of London. The illustration was published in 1858 during a bad cholera outbreak. After that, London had built the best sewers in the world to improve the situation. The river was much cleaner, the drinking water much safer, but filth on the streets had only increased.

Try sleeping in that environment. I’d want to cover my face for sure. To wear something over my mouth and nose might also have helped slightly to protect my lungs from the horrid air which was charged with soot particulates and sulfur dioxide from industrial and home use—heating and cooking—of coal burning. The poisons in the London air took the lives of thousands of people every year.

Then there were the human scavengers I spoke of, some desperate enough to take what they could off a sleeping man, despite the risks. Remember, leather and cloth were sellable. One might wake up without shoes or missing pieces of clothing. That’s assuming one woke up at all. Hungry children banded together to scavenge in groups, some of them, organized by adults known as kidsmen, were quite ruthless. Fagin in Oliver Twist was a kidsman.

I wouldn’t worry too much about the cats, but feral dogs…. Hmmm, my pup, Jasper, looks at me with a particularly sad expression when I consider writing about canines molesting sleeping humans, so I’ll just leave that up to my audiences’ imaginations.

—Alan M. Clark

Eugene, Oregon

Get a free ebook copy of The People of the Abyss from Project Gutenburg—available in various formats including Kindle and Epub, : http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1688

Preorder A Brutal Chill in August

Visit Alan M. Clark online: www.alanmclark.com

About Alan M Clark

Author and illustrator Alan M. Clark grew up in Tennessee in a house full of bones and old medical books. His awards include the World Fantasy Award and four Chesley Awards. He is the author of seventeen books, including ten novels, a lavishly illustrated novella, four collections of fiction, and a nonfiction full-color book of his artwork. Mr. Clark’s company, IFD Publishing, has released 44 titles of various editions, including traditional books, both paperback and hardcover, audio books, and ebooks by such authors as F. Paul Wilson, Elizabeth Engstrom, and Jeremy Robert Johnson. Alan M. Clark and his wife, Melody, live in Oregon. www.alanmclark.com