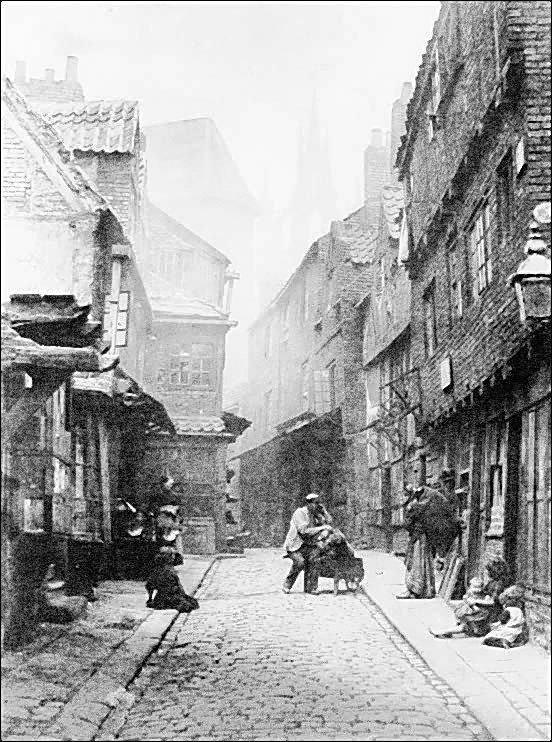

Historical Terror: Horror That Happened—London’s Murder Weapon

Detail from “In the Dark, In the Night” copyright © 2013 Alan M. Clark. Cover art for EAST END GIRLS by Rena Mason

Was Jack the Ripper a monster, larger than life, beyond our comprehension? From all that has been dramatized about the killer, one might think so. But no doubt the killer was merely a man, with the fears and frailties of an average human being.

If I could go through his pockets, I’ll bet I’d find that he carried common, everyday items that helped him maintain his physical and mental wellbeing in the world of Victorian London. If that’s true, it would tell me that although he was an extreme danger to society, he was subject to the physical and emotional trials we all go through in life.

“All that She’d Need” copyright © 2014 Alan M. Clark. Interior illustration for JACK THE RIPPER VICTIMS SERIES: THE DOUBLE EVENT by Alan M. Clark

The clothes we wear and the items we carry on our person say something about us. I wear shirts that button up the front. I never wear t-shirts. If asked why, I might say that I don’t think t-shirts are flattering to my middle-aged abdomen. I carry numerous keys because I want access to areas and items I lock up. One can easily deduce therefore that I’m doing more than most would to secure my stuff against theft, and that might say something about how many times I’ve been robbed. I slip my keys into a flexible glasses case before putting them in my pants because they chew holes in my pockets. I got tired of paying for new jeans just because the pockets were ruined, so it’s reasonable to assume I have been concerned about money during my life and learned to be frugal. I carry lip balm because I have the nervous habit of chewing my lips and making them chapped. What have I to be nervous about? That’s a good question. I carry a cloth handkerchief to wipe my nose instead of using paper tissues which might have something to do with my desire to preserve the natural world. For reasons I won’t reveal here, I carry a pocket knife and have no cell phone.

All these things say something about what I think and feel in my daily life, most of it of no consequence to anyone, but if I were a suspect or victim in a crime and the truth about me was important to discern, useful conclusions about who I am might come from considering these things.

Beyond the savagery of the Jack the Ripper killings, the murderer is perhaps most defined by his choice of victims; common, poor women who would have been forgotten in time if not for the compelling manner of their deaths.

With the idea that to know something of the women is to know something about the Ripper, I became interested in the possessions of the victims. The possessions of the murdered women, found at the crime scenes, provide a glimpse of their lives and speak volumes about the time in which the White Chapel Murderer lived. The people of 1888 London didn’t have the mp3 players and electronic tablets we have today. They didn’t have car keys, water enhancers, thumb drives, and anti-anxiety medications, but they did carry items useful to them in their time and circumstances.

Here are lists of the belongings of the first four victims of the Ripper as found at the crime scenes:

Mary Ann Nichols (Polly Nichols)

Clothing:

A black Straw bonnet trimmed with black velvet

A reddish brown ulster with large brass buttons.

A brown linsey frock

A white flannel chest cloth

A pair of black ribbed wool stockings

A wool petticoat stenciled with “Lambeth Workhouse”

A flannel petticoat stenciled with “Lambeth Workhouse”

Brown stays

Flannel drawers

A pair of men’s boots with the uppers cut and steel tips on the heels

Possessions:

A comb

A white pocket handkerchief

A broken piece of mirror (This would have been a valuable item for one living in the work house or common lodging)

Annie Chapman

Clothing:

A long black, knee-length figured coat.

A black skirt

A Brown bodice

An Additional bodice

Two petticoats

A pair of lace up boots

A pair of red and white striped wool stockings

A neckerchief, with white with red border (folded into a triangle and tied about her neck)

Possessions:

A large empty pocket tied about the waist, worn under the skirt.

A scrap of muslin

A small tooth comb

A comb in a paper case

A scrap of envelope containing two pills.

Elizabeth Stride

Clothing:

A Long black cloth jacket, trimmed with fur at the bottom

A red rose and white maiden hair fern pinned to the coat.

A black skirt

A black crepe bonnet

A checked neck scarf knotted on left side

A dark brown velveteen bodice

Two light serge petticoats

A white chemise

A pair of white stockings

A pair of spring sided boots

Possesions:

Two handkerchiefs

A thimble

A piece of wool wound around a card

A key for a padlock

A small piece of lead pencil

Six large and one small button

A comb

A broken piece of comb

A metal spoon

A hook (as from a dress)

A piece of muslin

One or two small pieces of paper

A packet of Cachous. (a pill used by smokers to sweeten breath)

Catherine Eddowes

Clothing:

A black straw bonnet trimmed in green and black velvet with black beads

A black cloth jacket with trimmed around the collar and cuffs with imitation fur and around the pockets in black silk braid and fur.

A dark green chintz skirt with 3 flounces and brown button on waistband.

A man’s white vest.

A brown linsey bodice with a black velvet collar and brown buttons down front

A grey stuff petticoat

A very old green alpaca skirt

A very old ragged blue skirt with red flounces and a light twill lining

A white calico chemise

A pair of men’s lace up boots. (The right boot was repaired with red thread)

A piece of red gauze silk worn around the neck

A large white pocket handkerchief

A large white cotton handkerchief with red and white bird’s eye border

Two unbleached calico pockets with strings

A blue stripe bed ticking pocket

A pair of brown ribbed knee stockings, darned at the feet with white cotton

Possessions:

Two small blue bags made of bed ticking

Two short black clay pipes

A tin box containing tea

A tin box containing sugar

A tin matchbox, empty

Twelve pieces white rag, some slightly bloodstained

A piece coarse linen, white

A piece of blue and white shirting

A piece red flannel with pins and needles

Six pieces soap

A small tooth comb

A white handled table knife

A metal teaspoon

A red leather cigarette case with white metal fittings

A ball hemp

A piece of old white apron

Several buttons and a thimble

Mustard tin containing two pawn tickets

A Printed handbill

A printed card calling card

A Portion of a pair of spectacles

A single red mitten

I have not included the possessions of the Ripper’s fifth victim, Mary Jane Kelly, because she was killed in her own bed, in her abode, and her possessions were not provided by the police reports in the same way.

These lists speak to me of women who had little of material worth in the world. Not one of them had any money. During the period in which they lived, unemployment and severe poverty were widespread in London. Regardless of whether the Ripper’s victims had few opportunities to live better lives or were responsible in large part for their predicaments, their legacy is pitiful and poignant. Items such as the brown stays, the comb, and the packet of Cachous suggest vanity or at least the need to maintain appearances. The tin of sugar, the one of tea, and the black clay pipes speak of a desire for creature comforts. The bloodstained rags, the pieces of soap, tooth combs (toothbrushes) were aids to bodily functions. Those things that are part of a incomplete set, such as the single mitten, and the broken items, like the partial pair of spectacles and the piece of a comb, suggest that nothing could be wasted; that everything, even if seriously flawed or deficient was irreplaceable.

With little imagination, the lists speak of skills, preparedness, resourcefulness and even aspirations on the part of these women. The list of Catherine Eddowe’s garments and possessions conjures for me the image of a Victorian-era bag lady, wearing many layers of clothing and carrying too many items in her bags (the many pockets, most of which were probably hidden under her top skirt). The only thing missing is the shopping cart. We have limited information about Eddowes’s life, and most of it leaves out the emotional aspects of her existence. We can assume she didn’t set out to become a bag lady, to be homeless and poor.

What events in her life led to her demise on the streets of London? How much of the way she lived was a result of the choices she made? What was beyond her control? Was she chosen randomly by her killer?

What events in her life led to her demise on the streets of London? How much of the way she lived was a result of the choices she made? What was beyond her control? Was she chosen randomly by her killer?

I became fascinated enough with the questions that I explored her life and presented possible answers in my historical fiction novel, Of Thimble and Threat, published by Lazy Fascist Press. Catherine Eddowes had led a hard life and was very ill at the relatively young age of forty-seven when she died. My impression is that her choices had something to do with securing her wellbeing and placing her at risk, but that much of her existence was beyond her control. A life of poverty in London was slowly killing her, and the final blow, London’s murder weapon so to speak, was Jack the Ripper.

Still fascinated with the environment of late Victorian London, I explored the life of Elizabeth Stride, the Ripper’s third victim, in fiction in Say Anything But Your Prayers, also released by Lazy Fascist Press. Having thus started a string of novels, I titled it Jack the Ripper Victims Series, and went on to write about his first victim, Mary Ann “Polly” Nichols in A Brutal Chill in August, which was released by Word Horde in August 2016.

I refer to the Ripper as male because of the name Jack, but of course we don’t know the gender of the killer. Although we can’t know much about the Whitechapel murderer, we have information that tells us something about him and offers a glimpse of the world in which he and his victims lived. We can surmise that he was in most ways as vulnerable as his victims in a dangerous, often merciless world, that he was no doubt as aware as they were of the need to maintain appearances and to achieve the highest social position possible in order to ensure survival in a swiftly changing environment, and that he probably understood that eventually disease and death would claim him without ceremony and that he would die, just like everyone else. Perhaps, as he considered these things, he was filled with a pitiable fear like that experienced by his victims.

I refer to the Ripper as male because of the name Jack, but of course we don’t know the gender of the killer. Although we can’t know much about the Whitechapel murderer, we have information that tells us something about him and offers a glimpse of the world in which he and his victims lived. We can surmise that he was in most ways as vulnerable as his victims in a dangerous, often merciless world, that he was no doubt as aware as they were of the need to maintain appearances and to achieve the highest social position possible in order to ensure survival in a swiftly changing environment, and that he probably understood that eventually disease and death would claim him without ceremony and that he would die, just like everyone else. Perhaps, as he considered these things, he was filled with a pitiable fear like that experienced by his victims.

Most of us spend much of life feeling confidently alive, solid and incorruptible, not thinking about our demise, our eventual loss of facility and faculty, our loss of awareness and identity and finally the decay of our flesh. Those of us who have not seen war or violent crime and disaster turn to face our demise slowly over many years as it dawns on us that we are just like those who have gone before us, that we all suffer and die. But to face that terror precipitously, to have the process demonstrated within moments, to be the playwright and director of that drama—that is what the Ripper experienced.

Could he identify with the women he’d murdered and feel their suffering? Having revealed to himself by his own cruel acts the heights of fear and pain and the terrifying frailty and ephemeral nature of flesh and awareness, was his dread of a particularly intense nature?

If his freedom or his life were never taken from him in answer to his crimes, did he at least suffer from the revelations of his own mortality? I would like to think that he did.

—Alan M. Clark

Eugene, Oregon

About Alan M Clark

Author and illustrator, Alan M. Clark grew up in Tennessee in a house full of bones and old medical books. His awards include the World Fantasy Award and four Chesley Awards. He is the author of seventeen books, including ten novels, a lavishly illustrated novella, four collections of fiction, and a nonfiction full-color book of his artwork. Mr. Clark’s company, IFD Publishing, has released 44 titles of various editions, including traditional books, both paperback and hardcover, audio books, and ebooks by such authors as F. Paul Wilson, Elizabeth Engstrom, and Jeremy Robert Johnson. Alan M. Clark and his wife, Melody, live in Oregon. www.alanmclark.com