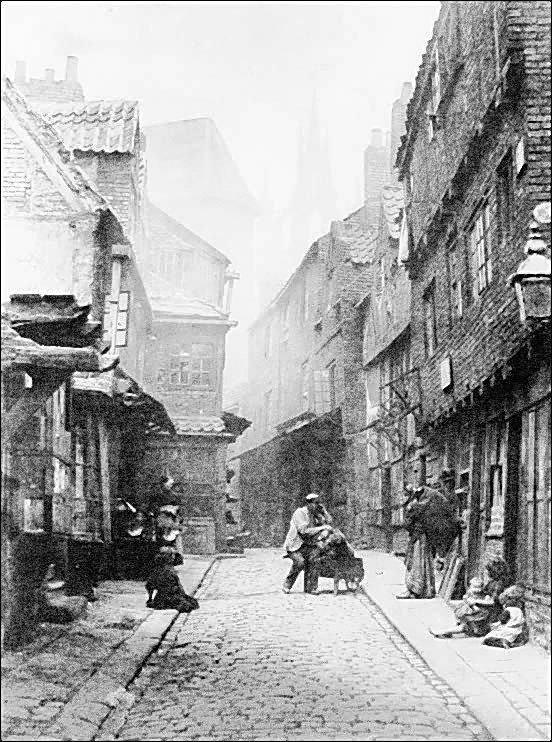

Chapter 19 is about overcrowding and the growing sprawl of the London ghetto in the East End. The housing was increasingly owned by what we would call euphemistically “slum lords,” but would more appropriately be called heartless, unprincipled criminals. With the overcrowding in the East End, the situation was a seller’s market for landlords, and the price to let a room went up, just as wages went down. Renters were paying 1/4 to 1/2 their earnings on housing while sharing one room with several others. Rooms were sublet and sub-sublet. One with a night shift at a job shared a room with one who had a day shift, and possession of the room was handed off between shifts. Space under beds was rented as a place to sleep. Jack London cites numerous heartbreaking cases of human neglect and degradation.

Chapter 19 is about overcrowding and the growing sprawl of the London ghetto in the East End. The housing was increasingly owned by what we would call euphemistically “slum lords,” but would more appropriately be called heartless, unprincipled criminals. With the overcrowding in the East End, the situation was a seller’s market for landlords, and the price to let a room went up, just as wages went down. Renters were paying 1/4 to 1/2 their earnings on housing while sharing one room with several others. Rooms were sublet and sub-sublet. One with a night shift at a job shared a room with one who had a day shift, and possession of the room was handed off between shifts. Space under beds was rented as a place to sleep. Jack London cites numerous heartbreaking cases of human neglect and degradation.

Toward the end of the chapter, Jack London said that the incidences of husbands beating their wives was quite high, that while men should have been committing the violence toward their employers, they instead took their frustrations out on women. I know that the laws protecting married women in England improved over the course of the 19th century.

Here’s a scene from A Brutal Chill in August. In it Polly Nichols has been severely beaten by her husband, then taken in by neighbors, Susan and Paul Heryford, for her protection. Polly’s husband, Bill, comes to collect her. The year is 1878.

“We fear for your safety,” Paul said to Polly. “You don’t have to go with him tonight. You can stay here.”

“I don’t have to listen to this,” Bill said. He grabbed Polly by the arm and turned toward the door.

“You would do well to listen,” Susan said. “What we have to say involves legal proceedings.”

Bill blustered, his brows knitting furiously and his mouth working to make the cruelest arching scowl, yet a shade of concern trembled in his eyes.

“I learned something of the law today,” Susan said. She stood and walked to a cabinet, opened a drawer, and pulled out leaves of paper folded together. “It so happens that Parliament amended the Matrimonial Causes Act earlier this year. If Paul and I provided testimony that you severely beat your wife, you might be convicted of the crime. If that came to pass, Polly would be within her rights to leave you, and you’d be required to provide a monetary maintenance to her for the rest of her life. The new law also allows for her to take the children.”

Bill’s eyes had become great angry orbs bulging from his red face. “You learned nothing of the kind! You are a wretched, meddling hay—” He glanced at Paul uneasily as the man took a step toward him. Mr. Heryford’s face became as hard and determined as any Polly had ever seen.

He’s looking for an excuse to strike Bill, Polly thought. While excited to have champions defending her, she feared further reprisals for her husband’s shaming.

“The company what employs you,” Paul said, “was among those the House of Commons tasked with printing and distributing the amendment.”

Susan held forth the publication.

Bill approached her slowly, then snatched the pages from her hand and tore them up.

“You might tear the paper, Mr. Nichols,” Susan said, maintaining her calm, “but the law remains, and now you cannot claim ignorance of it.”

“Now, as your boys are gone,” Bill said, sneering, “leading your husband around by the nose isn’t good enough? You’ve got to mind somebody else’s business. There’s little more despicable than a neighbor who listens through the walls for advantage.”

“There’s no call for you to mistreat my wife too,” Paul said. “You are no great specimen, sir. I could easily defend both women.”

“I can see you’d like to try.”

“Yes, sir, I would.”

Bill spun on his heels to face his wife. “Come, Polly, we’ll go home.”

“Take great care in how you treat your wife, Mr. Nichols,” Susan said.

Polly didn’t want to go with him. She was afraid. But she’d only delay the inevitable if she stayed, and to go seemed the best way to reduce his anger at the moment. He had been shamed and threatened. Although she found that satisfying, she feared that the Heryfords had fed his anger.

Polly Nichols and her family at the time were not among the wretched poor, so she had an advantage that allowed her to accept help from the neighbors. In a poverty stricken household, if the one dolling out the beatings was the major bread-winner, the family would go hungry if he were jailed, so most violence of that type went unpunished.

Jack London makes dire predictions for Great Britain’s future at the end of the chapter. History proved him wrong in many cases, but I can certainly see why he feared the worst based on what he witnessed.

Why didn’t the people of the abyss flee, travel to live in another city or even another country? For one, they hadn’t the means to flee. Sure one could up and leave town, but there remained the question of how to get by as a stranger elsewhere. And such downtrodden people frequently don’t have the imagination required for hope.

In my last post I referred to “magical bootstraps.” That is in reference to the expression “Pull yourself up by your own bootstraps,” meaning to better oneself by ones own efforts, yet the expression points to an impossible feat—to lift oneself into the air by pulling up on the straps attached to boots.

If such a thing is possible at all, either lifting oneself into the air by pulling up on the straps attached to boots or bettering oneself against difficult, perhaps prohibitive or forbidding odds, it will be done in the imagination. Once conceived in the imagination, the former remains impossible due to gravity, but the latter does become more possible. That’s assuming one has confidence in the use of imagination, a sense that once a course of action toward a goal is “seen” within the mind’s eye, hope and perseverance will carry one forward to the objective.

“Pull yourself up by your own bootstraps” was originally an ironical statement meant to indicate the impossible or nearly impossible, but in modern times the sense of that irony seems to have become lost. Those who feel they have succeeded in life and resent having to share what they’ve accumulated are sometimes heard to complain of the needy that they should “Pull yourself up by your own bootstraps,” as if doing so were an easy thing.

Yet, again, gravity in a symbolic sense often holds the needy down; the gravity of their situation. Can anyone actually pull themselves up by their own bootstraps” literally or figuratively without help from someone else? Perhaps, but it can seem in the face of steep odds a nearly impossible task. If you were malnourished, had few means, and were kept from opportunity by suspicion, disgust, and disdain for your class, how likely would be your success at bettering yourself and your situation?

Yet, again, gravity in a symbolic sense often holds the needy down; the gravity of their situation. Can anyone actually pull themselves up by their own bootstraps” literally or figuratively without help from someone else? Perhaps, but it can seem in the face of steep odds a nearly impossible task. If you were malnourished, had few means, and were kept from opportunity by suspicion, disgust, and disdain for your class, how likely would be your success at bettering yourself and your situation?

While imagination is powerful, like any trait, it varies from person to person. Some have it, some don’t. Whether one has it or not says nothing about the worth of the person. How many of our family and friends have the imagination to lift themselves into a better life without the help of others either more fortunate or more imaginative?

Magical bootstraps equals imagination plus hope.

—Alan M. Clark

Eugene, Oregon

Get a free ebook copy of The People of the Abyss from Project Gutenburg—available in various formats including Kindle and Epub, : http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1688

Preorder A Brutal Chill in August

Visit Alan M. Clark online: www.alanmclark.com

About Alan M Clark

Author and illustrator, Alan M. Clark grew up in Tennessee in a house full of bones and old medical books. His awards include the World Fantasy Award and four Chesley Awards. He is the author of seventeen books, including ten novels, a lavishly illustrated novella, four collections of fiction, and a nonfiction full-color book of his artwork. Mr. Clark’s company, IFD Publishing, has released 44 titles of various editions, including traditional books, both paperback and hardcover, audio books, and ebooks by such authors as F. Paul Wilson, Elizabeth Engstrom, and Jeremy Robert Johnson. Alan M. Clark and his wife, Melody, live in Oregon. www.alanmclark.com