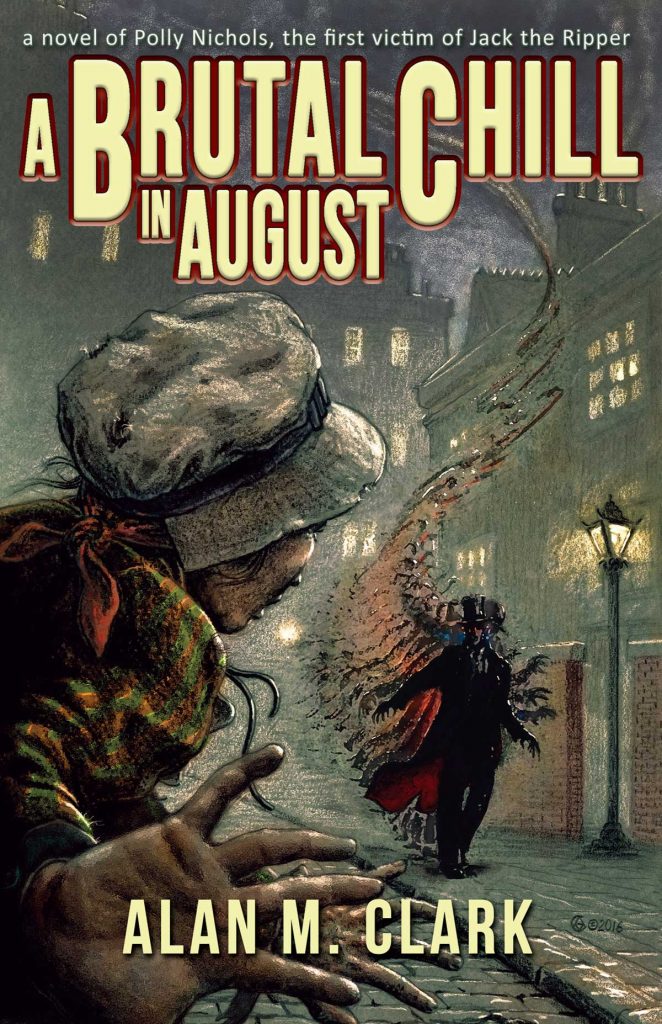

Christmas Ghosts: An Excerpt from Alan M. Clark’s A Brutal Chill in August

One of our favorite Christmas traditions, particularly popular in the Victorian era, is the telling of ghost stories. Something about the long nights of winter, the glistening of ice, and the clouds of breath that form as you step outside evokes the supernatural, the uncanny. Perhaps the most famous of these stories is Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, but other notable Christmas ghosts include Dickens’s “The Signalman,” M. R. James’ “The Diary of Mr. Poynter,” Edith Wharton’s “Afterward,” and H. P. Lovecraft’s “The Festival.”

With all that in mind, Word Horde is proud to present a new Victorian Christmas ghost story, in the form of this excerpt from Alan M. Clark’s stunning tale of Polly Nichols, first victim of Jack the Ripper, A Brutal Chill in August…

13

A Tempting Choice

On Monday morning, December 20 of 1875, Polly hid away the tinplate toys she’d bought for the children’s Christmas stockings—a steamship for John, a train for Percy, a horse-drawn carriage for Alice. As she imagined the children’s faces when they received their gifts, a knock came at her door. She answered the knock to find Judith had arrived early. Dorrie wasn’t with her. The cold and windy air outside tried to push its way in. Judith didn’t respond when invited to come in, so Polly stepped out and pulled the door shut.

“At first I couldn’t decide,” the woman said, “but I have, at present. Dorrie will begin school in the new year. She’s with her grandmother now and during the holidays. No longer shall I come on Mondays and Fridays.”

Perhaps Polly should have seen the day coming, since Percy was the same age as Dorrie, and he had already begun at the infants school. Polly had happily let go of her daytime duties of minding Percy, especially since the discovery she was pregnant again. She hadn’t told Bill or Papa about the pregnancy. Although she loved her children, she didn’t look forward to having yet another so soon.

Her surprise left her struggling unsuccessfully to think of a way to change Judith’s mind. Finally, Polly said simply, “I’m not prepared for the change.” Straining against the chill breeze, she knew she looked as if she might cry. “Could we do it just a bit longer until I can make other plans?”

Judith appeared unmoved. “No, I shall not have a child to keep during much of the week and shan’t need your help. I have plans for Christmas to think about today.”

Indeed, she wasn’t a good friend.

Polly hung her head wearily. “You’re lucky you don’t have the quick womb I have.”

“Are you knapped again?” Judith asked with a frown.

“Yes.”

“It’s not my luck,” Judith said. She grimaced slightly, then asked, “Haven’t you asked Bill to wear a sheath on his manhood?”

“He won’t.”

“Swaine does, and when that fails, I know how to end a pregnancy. There’s a woman can help you.”

“The Church tells us that’s murder.”

“Yes, well, a life unloved and spent in poverty,” Judith said, coldly, “what’s that?”

Polly had no answer. Judith started to turn away.

“Please,” Polly said, “I must have a drink today.”

“And that’s the difference between us,” Judith said. Shaking her head, she turned and walked away.

Polly stepped back inside, and slammed the door, shutting out the biting cold.

The woman’s abrupt manner aside, her suggestion about abortion made Polly uncomfortable because of the tempting option the procedure presented. She considered abortion wrong, and believed that if she took the option, she’d be guilty of murder. Apparently, Judith had chosen just such murders in the past.

Still, Polly believed the life in her womb would be better off if it never saw the world. With each child she’d had, her ability to provide for them, the time she had to share with them, her capacity for affection, and, yes, she admitted to herself, even to love them, had diminished.

What had Judith said? “A life unloved and spent in poverty.”

Perhaps if God knew how Polly felt, He would help. Yet, the Lord should know already what she held in her heart, even if the feelings were a jumble. Polly wanted the best for the three children she had, and if that meant she shouldn’t have another mouth to feed, another heart to soothe and love, then possibly He should take the infant in the midst of her pregnancy. The idea that she might have a miscarriage gave her a small hope which she knew must be dismissed, but which she clung to for fear that if she didn’t, God might not know her preference. The conflict within her turned to nausea. Although most likely mere morning sickness, the discomfort bore with it a chilling uneasiness.

She didn’t have time for such distraction, and tried not to think about the matter further. Her schedule for the afternoon required her to print a broadsheet that advertised a boxing match. She had the materials, including a nicely done woodcut of men preparing to punch each other while others in the background cheered. She needed to take care of Alice first. As she occupied herself, stoking the fire, cleaning the dishes and the pot used to prepare the meal from the night before, nausea and disquiet continued to hound Polly. Her hands trembled and her heart periodically hammered in her chest.

Finally, she promised herself that she’d find a moment to say a prayer for the infant in her womb and one for Judith. That did little to calm her.

She hurriedly fed Alice a midday meal of bread and butter, then placed her in the bed, wrapped in a faded red wool blanket, hoping the girl would take a nap. Before beginning work on her broadsheet, Polly found her moment for prayer. Alice had become quiet, and a calm came into the room, but not into Polly. The conflict in her heart had turned to an unaccountable foreboding. She voiced the words before she’d had a chance to think them through.

“Please O Lord, take this child now before it’s too late.” Polly regretted her plea immediately. While trying to persuade herself that God understood that she meant for the child not to suffer, she knew her true motive to be self-serving. After years of carefully avoiding any mention of herself in prayer, she’d found a new way to demonstrate her selfishness to God. She quickly said the penitent prayer from Mr. Shaw’s well-worn card, but she didn’t feel any better.

Polly couldn’t do her work. Feeling naked before the eyes of the Lord, she paced. When Alice began to stir, Polly knew she disturbed the child’s slumber. She had to get away.

Stepping outside, she had the intention of pacing the lane’s granite footway outside her door. Having traveled half a block up Trafalgar Street, she decided she should keep going. She imagined walking the two or more miles to the docks, and stowing aboard a ship headed to some land where people believed in a different god, one who would not know her so well.

Then, she remembered she’d left the front door open. She broke out in a sweat. Her heart moved uncomfortably as she thought of a stranger entering her room while Alice slept. She imagined John and Percy coming home from school to find nobody home, their confusion and sadness when they found out their mother had abandoned them, and so close to Christmas!

Polly turned and walked back the way she’d come.

Although the shame had become so large inside her that she saw little else, she knew that her children needed her.

* * *