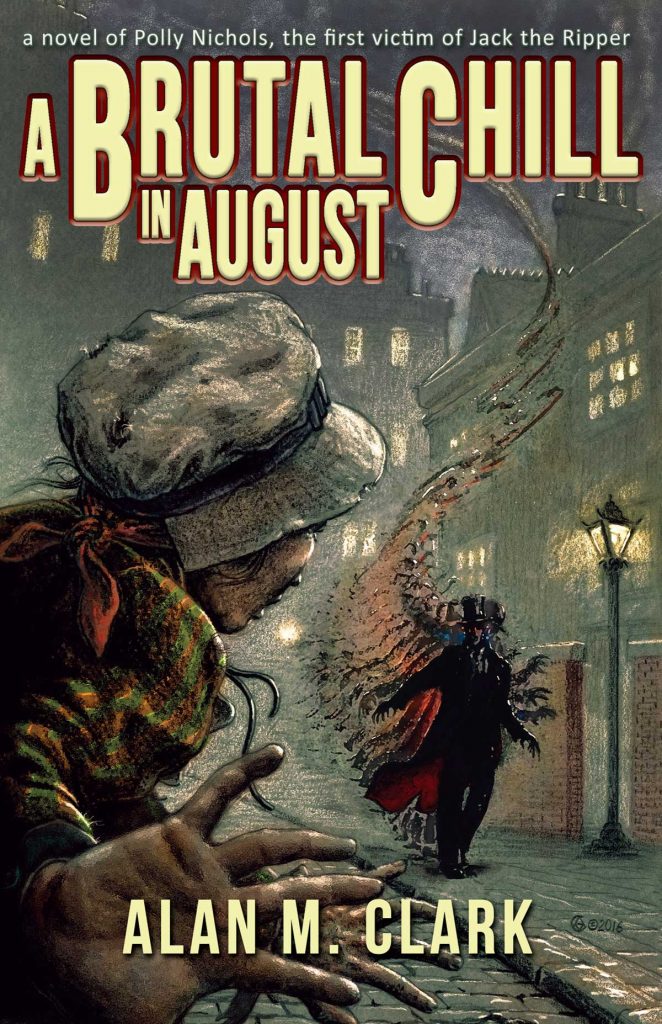

It was the proverbial dark and stormy night. Cold rain soaked London, lightning streaked a sky already lit orange by a pair of dock fires, and thunder rumbled menacingly. Despite the inclement weather, Polly Nichols, born Mary Ann Walker some forty-three years earlier, walked the streets of Whitechapel, hoping to earn enough to pay for that night’s lodging. Polly was pretty for a girl of the streets, looking a decade younger than her true age, with delicate features, frosted brown hair, and gray eyes. For the price of a large glass of gin, one could have Polly, if one were so inclined.

And gin was Polly’s vice. Her twenty-four year marriage to William Nichols–which had produced five children–had ended in 1881 over Polly’s drinking, and the next few years found Polly bouncing from home to home, including her father’s house, a cohabitation with a blacksmith named Thomas Dew, infirmaries, “sleeping rough,” and workhouses. In May 1888, Polly found a job as a live-in servant for Sarah and Samuel Cowdry, the Clerk of Works in the Police Department. In a letter to her father, Polly writes, “It is a grand place inside, with trees and gardens back and front. All has been newly done up. They are teetotalers and religious so I ought to get on. They are very nice people, and I have not too much to do.”

But the temptations of vice and drink prove too much for Polly, and in July 1888 she leaves the Cowdrys, stealing clothing valued at three pounds, ten shillings. Polly lives at one lodging house, then another, sharing rooms and paying her doss nightly. That evening of August 30 leading into the morning of August 31, 1888, Polly had already earned her keep and spent it on drink three times.

At two-thirty on the morning of August 31, Polly meets Emily Holland, a former roommate, who would later recall that Polly was “very drunk and staggered against the wall.” As they chat, church bells chime the half-hour. Polly staggers away, heading east along Whitechapel Road. Emily is the last friendly soul Polly meets.

At about three-forty, two men, Charles Cross and Robert Paul, discover Polly’s disheveled body while on their way to work. Her skirt is raised, exposing her. Cross is sure the woman is dead, but Paul believes Polly to be alive, breathing faintly. Paul rearranges Polly’s skirts to cover her and the two men seek a policeman.

Polly is discovered shortly thereafter by constable John Neil. He is soon joined by constables Thane and Mizen, the latter of which had been summoned by Cross and Paul. The policemen call Dr. Rees Ralph Llewellyn to the scene, and he pronounces Polly dead at 4:00. Time of death is estimated at 3:30.

Following the police inquest into Polly’s death, The Times reported: “There was a bruise running along the lower part of the jaw on the right side of the face. That might have been caused by a blow from a fist or pressure from a thumb. There was a circular bruise on the left side of the face which also might have been inflicted by the pressure of the fingers. On the left side of the neck, about 1in. below the jaw, there was an incision about 4in. in length, and ran from a point immediately below the ear. On the same side, but an inch below, and commencing about 1in. in front of it, was a circular incision, which terminated at a point about 3in. below the right jaw. That incision completely severed all the tissues down to the vertebrae. The large vessels of the neck on both sides were severed. The incision was about 8in. in length. The cuts must have been caused by a long-bladed knife, moderately sharp, and used with great violence.

“No blood was found on the breast, either of the body or the clothes. There were no injuries about the body until just about the lower part of the abdomen. Two or three inches from the left side was a wound running in a jagged manner. The wound was a very deep one, and the tissues were cut through. There were several incisions running across the abdomen. There were three or four similar cuts running downwards, on the right side, all of which had been caused by a knife which had been used violently and downwards. The injuries were from left to right and might have been done by a left-handed person. All the injuries had been caused by the same instrument.”

Rumors, compounded by the press, spread throughout Whitechapel, many blaming shoemaker John Pizer, a Polish Jew known as “Leather Apron.” Although there was scant evidence, Pizer was arrested and questioned, though he was released shortly after his alibi checked out. Pizer later sued at least one newspaper and won compensation over the paper’s libelous claims that he was the murderer.

As for the real murderer, Polly would not be his last victim. And soon, the world would know his name.

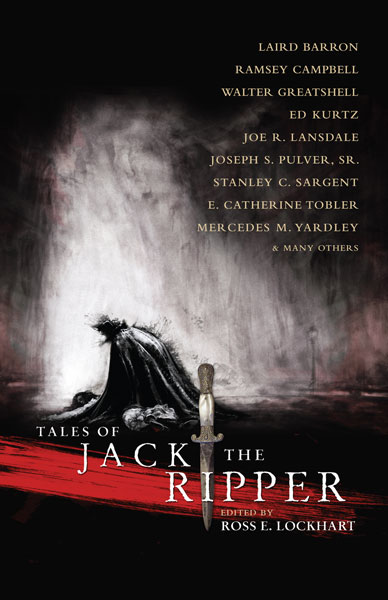

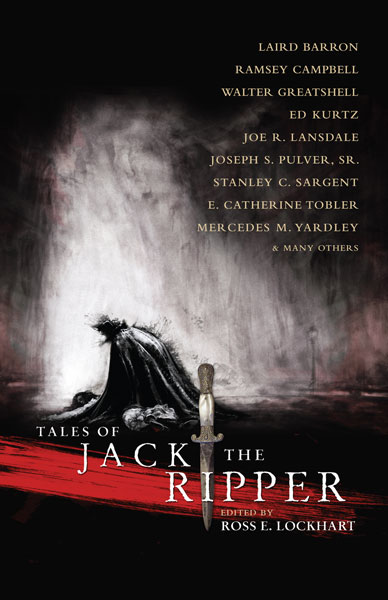

This post is brought to you by Tales of Jack the Ripper, an anthology of seventeen stories and two poems examining the bloody legacy of the most famous serial murderer of all time. Ask for Tales of Jack the Ripper by name at a bookseller near you, or order the Saucy Jack Deluxe Pack from Word Horde.