THE PEOPLE OF THE ABYSS Liveblog Part 4 by Alan M. Clark

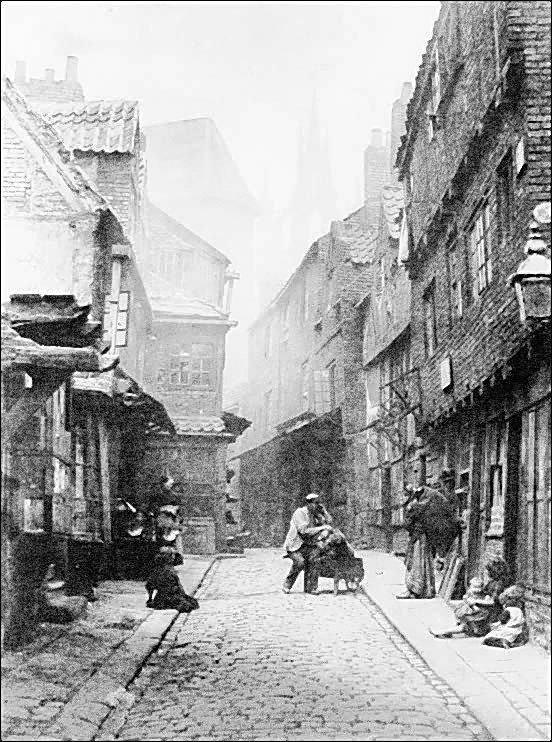

In chapter 4, Jack London found an affable fellow to room with. The author engaged him in conversation, and learned that the man was a hapless seaman, 22 years old, who had no aspirations for better work, starting a family, or truly anything other than earning the necessary funds to feed his drinking habit. If he didn’t want family, was it because he saw something like the image above in his mind’s eye when he imagined it? Despite seeming beaten down by crushing poverty and having no drive for anything better, the man was likable and intelligent and had a sense of humor. His father was a heavy drinker, and that seemed to be an acceptable course for the young man.

In chapter 4, Jack London found an affable fellow to room with. The author engaged him in conversation, and learned that the man was a hapless seaman, 22 years old, who had no aspirations for better work, starting a family, or truly anything other than earning the necessary funds to feed his drinking habit. If he didn’t want family, was it because he saw something like the image above in his mind’s eye when he imagined it? Despite seeming beaten down by crushing poverty and having no drive for anything better, the man was likable and intelligent and had a sense of humor. His father was a heavy drinker, and that seemed to be an acceptable course for the young man.

The only ones lower in station than this man in British society of the time were the “unfortunates,” those chronically unemployed or unemployable people who begged on the streets. Even his manner of speaking, his accent and the vernacular of his speech, which the author recorded with some attention to detail, no doubt marked him as one of the lowest class. That alone would have stood in his way had he tried to climb the ladder of success. Although perhaps not satisfied with his lot in life, the man seemed pleasantly resigned to it.

I am an alcoholic, 26 years sober. I emerged from a particularly sad state because of the love of family and friends, but most of all because there are survivors of alcoholism who know something about what it takes to live with such a disease and remain sober, and who were willing to help me. That’s primarily a result of Alcoholics Anonymous, AA for short. Before AA, virtually all alcoholics perished with or from the disease. If they did not die from an accident that mortally wounded, or ended up in an asylum for the mentally-ill, then they died a slow death from the over-exposure to alcohol that destroys internal organs, especially the liver. AA came into existence in 1935. It’s success rate is difficult to calculate, and has been placed as low as 3% and as high as 40%. I’ve heard slightly better statistics concerning substance abuse treatment, many forms of which incorporate the 12 step program of AA. In my life, despite the low numbers, I could see human beings surviving alcoholism. That helped me to have hope.

Perhaps the poor sot Jack London found did not see any alcoholics surviving their illness. In a time when physical comfort and an easy way to unload stress was badly needed by the down and out, and much of the available sustenance took the form of alcoholic beverages, the culture was saturated with substance abusers, the condition perhaps seeming to be quite natural and acceptable. Many saw alcoholic drink as a reasonable alternative to other foods.

Still, being a drunkard in that environment? I’d want to have my wits about me to more effectively compete for resources, jobs, and shelter, unless I merely had no hope. In that case, I suppose I might fear being fully conscious and feeling the low grade pain of hunger, the anxiety of thinking about finding shelter and my next meal. Perhaps a permanent buzz providing a certain level of anesthesia would seem a good idea.

If he had no hope, what, then, accounted for the man’s sense of humor and affable nature? I’ve found in my research into the Victorian era poor that they seem to have had a reservoir of vitality despite their predicament. I suspect that it is as simple as the fact that they only knew what they had, and what others of their kind had, and had had for generations. They had their place within a culture of dramatic inequality, but that was the way it had always been. Envy and coveting served little useful purpose in a situation in which one needed to focus what energy and faculty was available on the day to day grind of survival.

That’s not to say that there wasn’t much crime and occasional unrest. I’m merely surprised there was no more than there was. Perhaps lack of contrast plays a role as well, since these people did not wake up one morning after living most of their lives with 21st century standards to find themselves in such aching poverty. No—as Jack London points out eloquently, they got there through generations of moving in that direction.

One of the reasons I enjoy writing the tales of the Jack the Ripper Victims is that it gives me the opportunity to contrast what people had then with what we have now. Few more powerful means exist in communication than this sort of contrast to help break through the complacency many of us don so easily in modern times.

—Alan M. Clark

Eugene, Oregon

Get a free ebook copy of The People of the Abyss from Project Gutenburg—available in various formats including Kindle and Epub, : http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1688

Preorder A Brutal Chill in August

Visit Alan M. Clark online: www.alanmclark.com

About Alan M Clark

Author and illustrator Alan M. Clark grew up in Tennessee in a house full of bones and old medical books. His awards include the World Fantasy Award and four Chesley Awards. He is the author of seventeen books, including ten novels, a lavishly illustrated novella, four collections of fiction, and a nonfiction full-color book of his artwork. Mr. Clark’s company, IFD Publishing, has released 44 titles of various editions, including traditional books, both paperback and hardcover, audio books, and ebooks by such authors as F. Paul Wilson, Elizabeth Engstrom, and Jeremy Robert Johnson. Alan M. Clark and his wife, Melody, live in Oregon. www.alanmclark.com